“It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma…

Uncovering the Chinese Semiconductor Market

Winston Churchill famously declared: "It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma." he continued: “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is the Russian national interest.”

The quote could equally well be used about the Chinese Semiconductor industry, shrouded in statistics, market research and forecasts that never connect. While Western semiconductor companies boast about every cent they give back to their investors every quarter, China has been busy working “the decade”.

The AI boom has genuinely been a blessing for the Chinese semiconductor industry. As the spotlights have been on Nvidia and the leading edge, the Chinese have been busy conquering all the other parts of the semiconductor industry, but the leading edge logic.

Don’t get me wrong. GPUs for AI are essential for China, but that is a different battle altogether. The long-term battle is first and foremost for the entire Chinese manufacturing base and the supporting semiconductor industry.

For half a decade, first the US military and later all the US administrations have had China in their crosshairs as it dawned that the US military complex was wholly dependent on semiconductors from Taiwan. Initially, the worry was not so much the Chinese semiconductor industry but more the fear of an invasion of the silicon island.

The tool embargoes barring the Chinese from acquiring expensive light and magic from Holland were more aimed at the future rather than an immediate fear of Chinese supremacy. Huawei was thrown into the bag as the Chinese tech company was hugely successful in sweeping across the telecom industry, winning 5 G contracts and securing the cable networks of Europe. There is a thin line between what is “national security” and “industry benefit”.

The fear was that there would be a backdoor in the Huawei equipment, which I have always found funny, as there certainly are backdoors in the US equipment. In Europe, we don’t do stuff like that because of GDPR - I know - that is really funny.

The view of the Chinese semiconductor market is more impacted by political rhetoric than by tangible data, and this is not likely to change in the near term. This also means the topic of China and Semiconductors is tribal and ingrained into the nationality of certain nations. Data and facts are now seen as patriotic or non-patriotic depending on what they show. It has become more important where you are from than what you are saying.

My work and analysis are driven by curiosity, and I honestly don’t care who is “winning” or what that even means. I don’t care if a fab is constructed in the Rose Garden in the White House or the Forbidden City of Beijing.

I have tracked the industry for so long that I understand it is constantly under reconstruction and rapid evolution. Driven by my curiosity, I spend time making sense of the industry.

While many in the industry live happy lives without having to understand the big picture (Hey, Claus - I have a boss, a spouse, kids and bills to pay..) I am not built that way. I need to understand what's happening and why. With a bit of luck, that can lead to what is next.

Fortunately, a few semiconductor leaders share my belief that a great strategy begins with the question: “What is going on?” and that it has to be answered with brutal honesty. The corporate candyfloss is sticky, but it has to go. This is how I make my living. I am the neutral and honest voice in the strategy process, and I bring independent and unbiased facts.

There are many examples in the semiconductor industry of companies missing the shifts, often memory companies that got killed by the whiplash of the cycle, but most notable have been the failures of Intel. Nobody in this industry is sufficiently large to ignore the shifts in the industry. It is vital to understand these shifts.

As my readers will know, I am following four significant shifts at the moment:

AI and its impact on the supply chain.

US trade policies from Embargoes to tariffs to Subsidies

The decline of the Hybrid business model

China

It is time to attack one of the most complex shifts in the Semiconductor industry—the path to Chinese self-sufficiency.

Wicked problems

I have to confess that I have an MBA. This means that, according to Elon Musk, I will never become a billionaire (true) or become capable of doing any real work (maybe true). It also means that I will end up at McKinsey (false) and be good at PowerPoint slides (true).

Most people think that MBAs are taught to use a particular toolbox and, similarly, solve problems the same way, but most people have never taken an MBA. The reality is that an MBA is a personal journey that has two main components: A hard skills track and a leadership track focused on personal development. People don’t follow you because of your engineering/financial/legal, or HR skills. No two MBA journeys are the same.

My journey started with a conversation with one of my professors, where I vented my frustration with the course. Every module made my life more difficult by uncovering complexities I had been blissfully unaware of. His reply was: “It will all make sense at the end of the MBA”

A couple of years later, at my graduation ceremony, I asked him what he meant. He replied that through the journey of uncovering complexity, we taught you to handle complexity. The world is incredibly complex, but there are ways of handling the complexity.

The term “The world is becoming increasingly VUCA” describes this best for me. VUCA stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous. And the Chinese market is the pinnacle of VUCA in the semiconductor world.

You have now been warmed up (and warned) to a journey into the thorny morasses of the Chinese semiconductor market, and no simple conclusions will be drawn. That is no excuse to dodge an analysis.

The Chinese Semiconductor Market

The Semiconductor Industry Association, or SIA, is the advocacy and lobbying organisation of the US semiconductor companies. While it is certainly not neutral, it is not aligned with the view of the US government, but it certainly has an interest in investments in the US semiconductor industry. As an example, the SIA has lobbied for the full implementation of the Chips Act while advocating against the embargoes against China, as it would hurt the members.

The World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, or WSTS, is a non-profit, member-based organisation that is seen as the iron-clad data source for the industry since its inception. It receives members’ trade data through data collection agents, who anonymise the data so that no competitive information can be found.

Although WSTS has less than 50% of the Semiconductor revenue as direct members, it cooperates with SIA and other regional trade organisations to obtain data. These procedures are similar to the WSTS procedure.

One area that lacks this arrangement is China, which has no such organisation. While WSTS has a good view of the sales of Western companies in China, it has little direct information on what Chinese manufacturers are selling to Chinese customers.

The WSTS method of developing data on the Chinese market is not described anywhere, so it is hard to judge its validity.

What is clear is that the Chinese semiconductor companies and their CCP stakeholders have no interest in giving the West good insights into the actual state of the Semiconductor Industry in China.

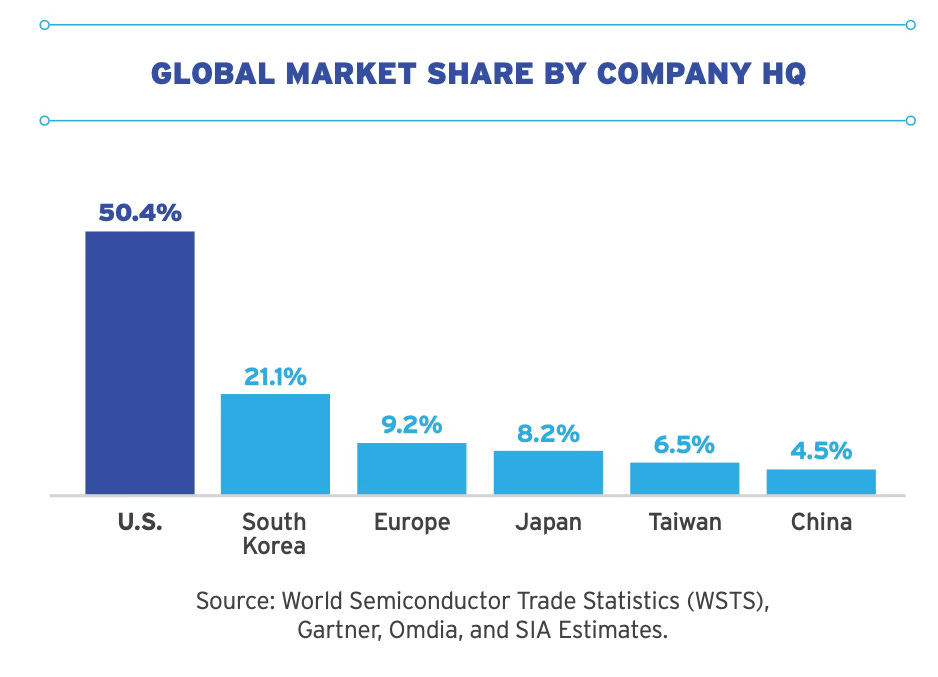

The SIA, in its most recent report, State of the US Semiconductor Industry, shows an overview of the market share by country based on the Company HQ.

What is interesting is that SIA references several sources for this data, which should not be necessary if SIA believed in the WSTS data. It even includes “SIA estimates”, and this can only be a reference to China, as WSTS has data from the other countries.

The other interesting observation is the very low market share for Chinese companies. After decades of intense investments, China is only at a 4.5% share?

While this is the market share of sales and not manufacturing, why did the US need to start the Chip Wars? What is all the fuss about?

A voice of reason in the post-truth world is Jeffrey Sachs. He is an American economist and professor at Columbia University, known for his work on global development, sustainability, and economic reform. In a speech at the Antalya Diplomacy Forum (I don’t have time to describe the ancient word diplomacy other than it is a lot cheaper than war), he highlighted that most of the wealth in the world was created by trade activities and that the US trade war with China was based mainly on envy of an economically succesfull nation. Even if this goes against your belief system, I propose that you get a dose of common sense and a calm overview of the current state of the trade policies.

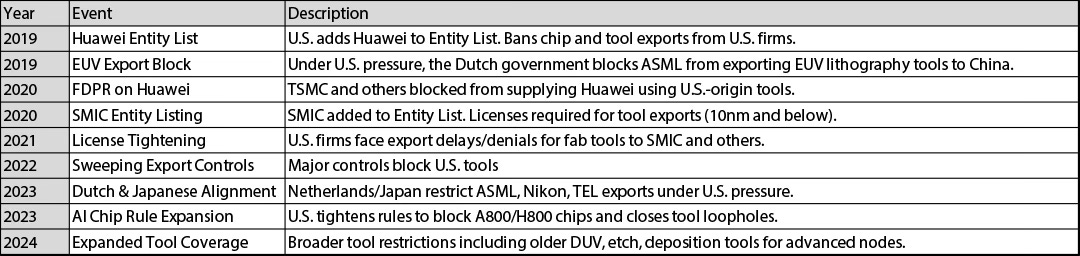

The Semiconductor embargos began in 2019 with the addition of Huawei to the entities list.

Before that event, China had not focused on semiconductor tools. The aim was to increase semiconductor manufacturing in China to capture a large value share of the electronics manufacturing in the country.

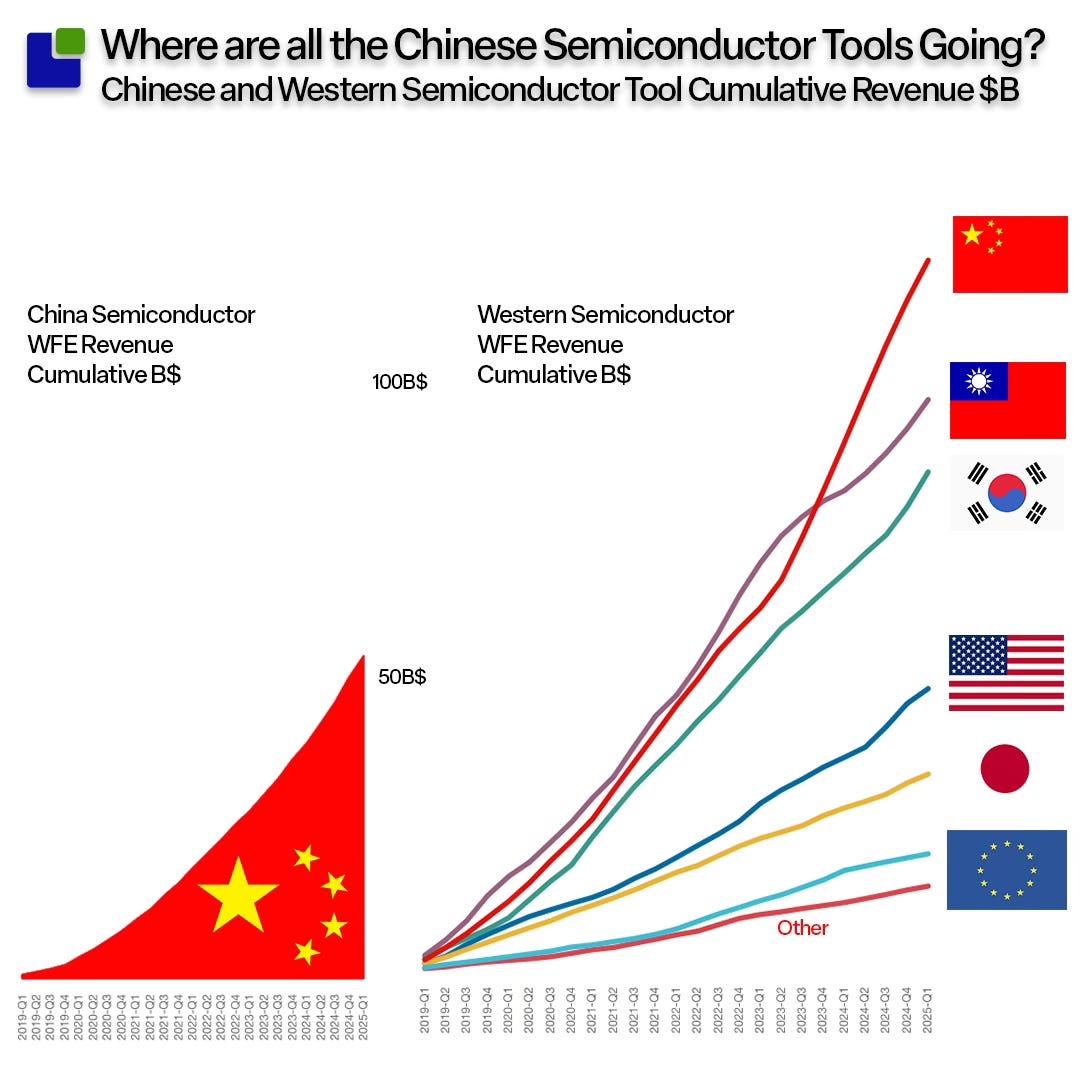

The semiconductor tool revenues of Chinese companies were below $600K, which has now grown to $4B. Also, China’s appetite for Western tools increased, especially after the ratification of the Chips Act.

While embargos have an effect, it is rarely the intended one.

If you believe that it is imperative for the US to dominate the semiconductor industry, not only from a design and incorporation perspective, but also from a manufacturing perspective, there is certainly cause for alarm.

The cumulative tool sales to China are outstripping all other countries when you add the internally manufactured tools that are only sold to Chinese companies.

The question is - where are all of these tools going if SIA believe that the Chinese companies only command a 4.5% share of the global Semiconductor market?

Using the WSTS numbers, the global market for Semiconductors and China's share are shown below.

Interestingly, this shows that the Chinese market has been in decline since 2019, when the Chinese market peaked at 36% of the total market. This goes against the general narrative in the political circles that Chinese dominance is increasing. While the AI boom has increased the share of the US market, this is a relatively new effect that began in late 2023.

This also corresponds poorly to the increasing tool sales. Even if the Chinese manufacturing base was embryonic, a cumulative purchase of $175B of semiconductor tools should be showing up somewhere. Where are these tools going?

The Chinese Statistics Riddle

Apart from wanting to obfuscate the real situation about the Chinese semiconductor industry, the Chinese Statistics are surprisingly friendly in giving a multitude of datasets about the Chinese semiconductor industry.

That is, until you find out that the data is sometimes being discontinued, and other times it is hard to get to the exact definitions of the terms.

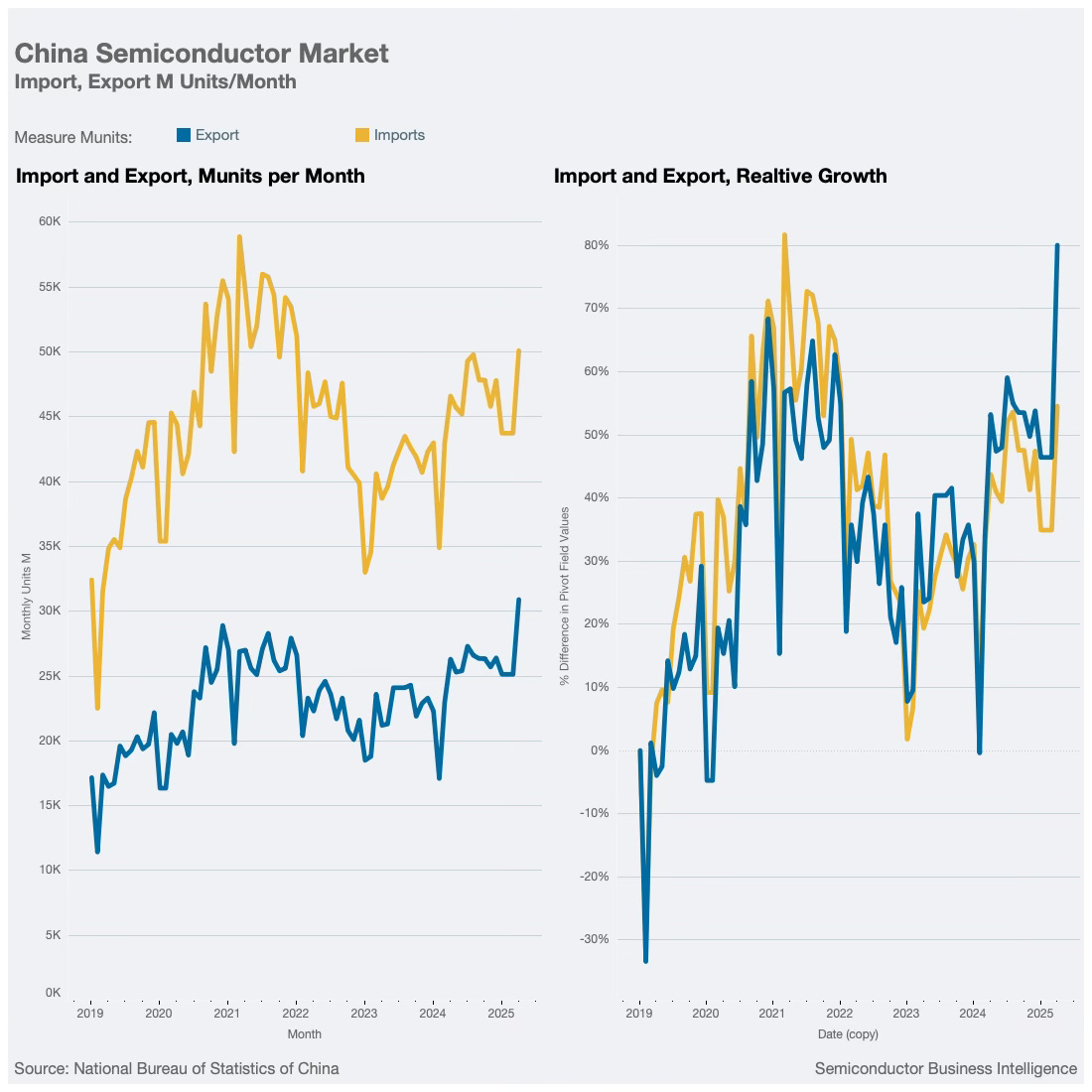

A good starting point is to look at the import and export of Semiconductor devices from a unit perspective:

Apart from the interesting development in April, there are a few other oddities in the data, as Imports and Exports are quite synchronised and the volumes are pretty high.

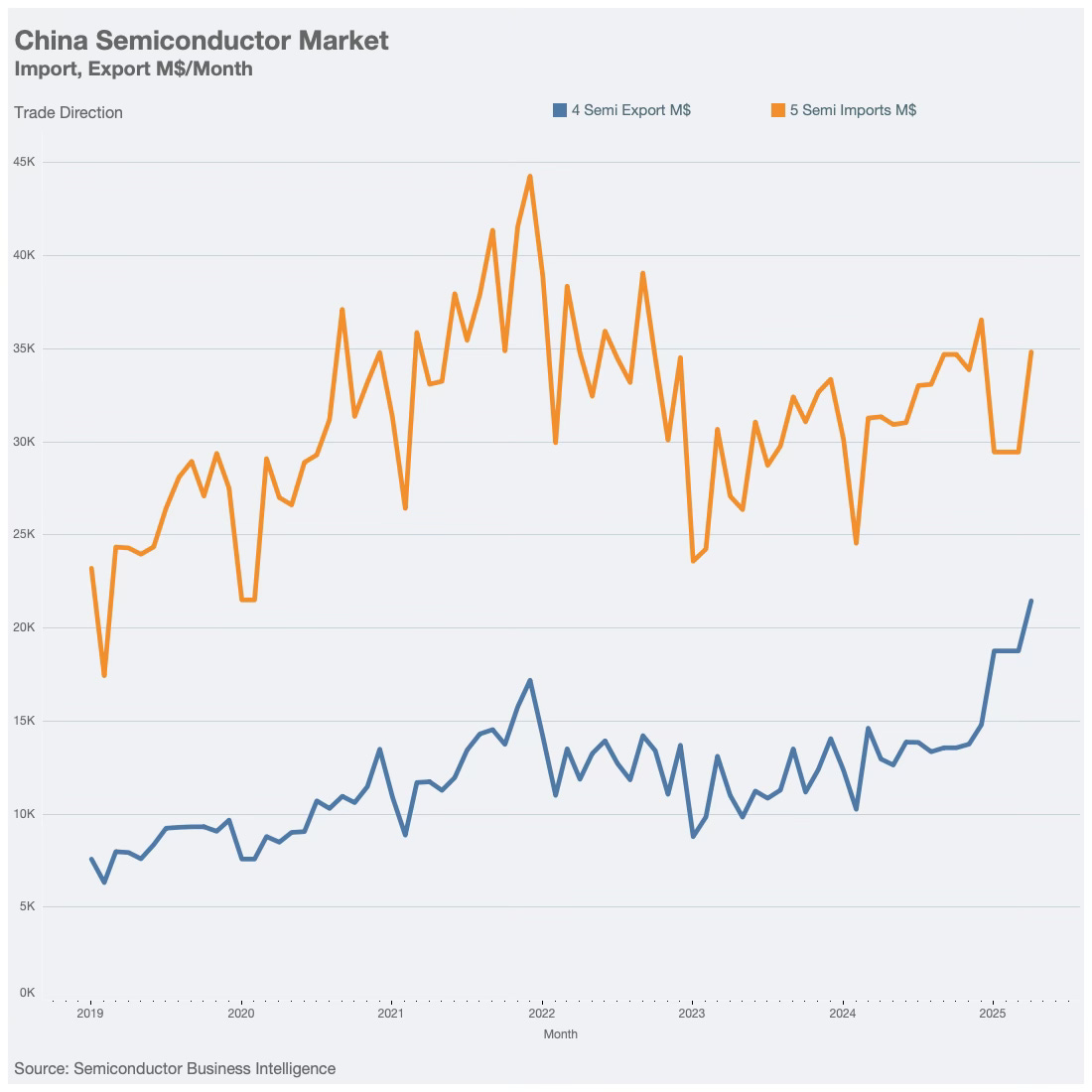

This is confirmed by the import and export value, as can be seen below:

The latest full quarter export is valued at more than 88B$ while the import value is over 56B$. This is entirely out of whack with the WSTS market estimation of $47B. Although Import and Export are not the same as what is sold into the Chinese market, I would have expected them to be in the same ballpark. There is undoubtedly more to unpack here unless China is running the most extensive cover-up since the moon landings or the Epstein files. Just kidding, I meant since the Great Rock and Roll Swindle.

A deeper dive into the Yangtze River

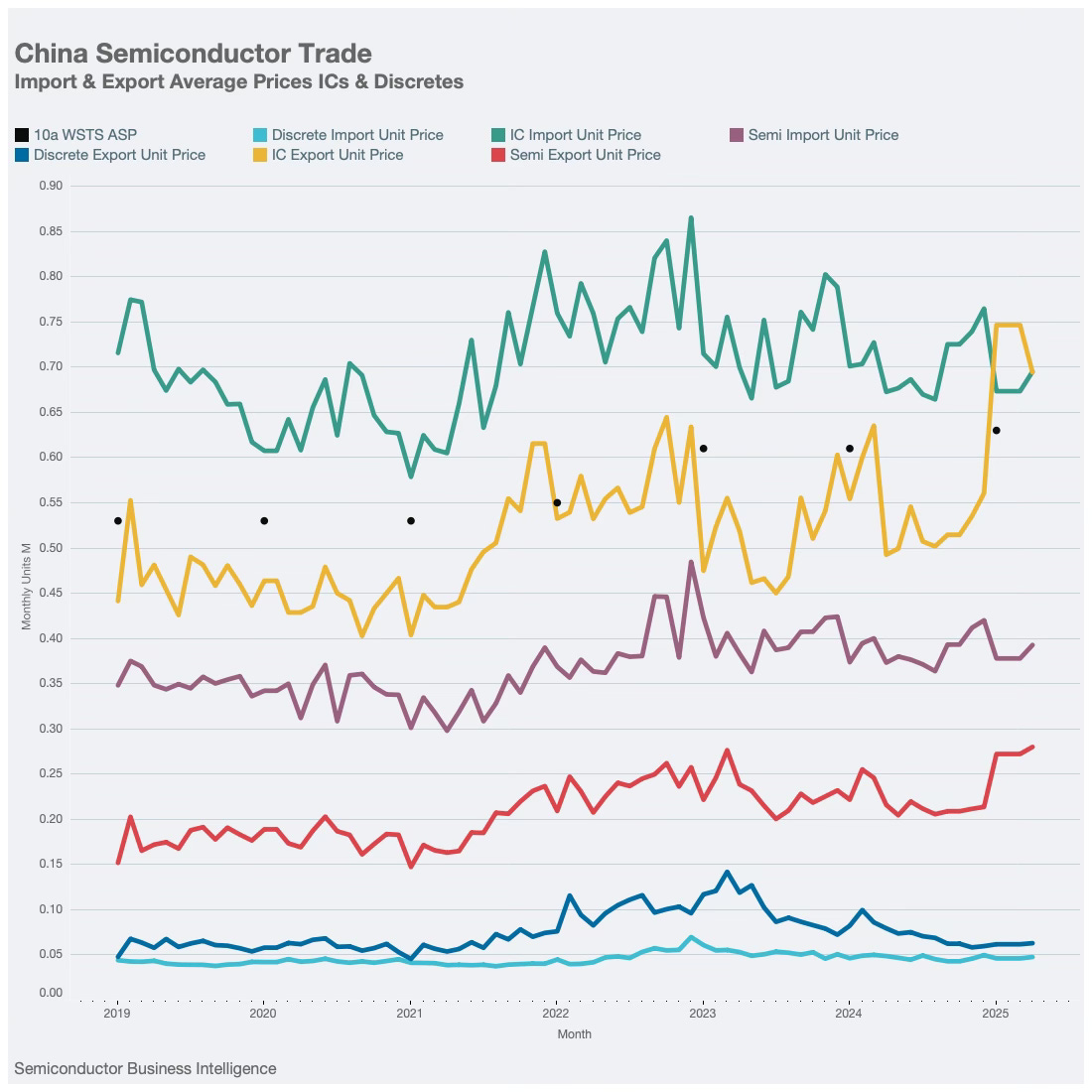

To gain more insight into the trade data of China, it is necessary to break up semiconductors into Integrated devices (ICs) and discretes, as these two categories can skew export unit prices quite dramatically.

As can be seen in the unit price analysis below, the two categories have quite different unit prices and need to be separated.

There are three categories shown together with the average WSTS global average selling price as a reference that includes both IC and discretes.

Apart from the two categories, a blended price is also shown.

The first observation is that the Import price of ICs is higher than the Export price, while it is the other way around for discretes.

The other observation is that the IC Export price is not far from the WSTS selling price. These two observations can unravel some of the conundrums surrounding the trade data.

Especially the discrete curves are interesting. Why did an exported discrete product become 2x more expensive than an imported one in the early parts of 2023?