More Semi Dollars without Collars

The people less growth of the Semiconductor industry

From a quiet existence in a universe full of nerds and specialists, the semiconductor industry has been propelled to the centre stage of global economics and security concerns. In the good old days, your dinner partner would turn to the other side when confronted with your sad choice of industry, but today, things have changed. I am struggling to eat while I answer questions about Nvidia’s stock price, ASML moat and my opinion on Pat Gelsinger’s departure. The industry has grown up and everybody understands its importance for future economic development.

The US hunger for fabs on American soil combined with the AI revolution has made it clear that investments in the industry are massive, and many people are needed to fill the big boxes rising from the suburban outskirts.

Several reputable companies and institutions are warning about the future semiconductor talent crunch:

Deloitte: With an estimated more than two million direct employees worldwide in 2021, Deloitte predicts that more than one million additional skilled workers will be needed by 2030, equating to more than 100,000 annually. For context, fewer than 100,000 graduate students in the United States are enrolled in electrical engineering and computer science annually (Link).

McKinsey proposes focusing on retention: Companies must cast a wider net, improve their employee value proposition, and get more out of their existing workforce. (Link)

SIA: We project the semiconductor industry’s workforce will grow by nearly 115,000 jobs by 2030, from approximately 345,000 jobs today to approximately 460,000 jobs by the end of the decade, representing 33% growth. Of these new jobs, we estimate roughly 67,000—or 58% of projected new jobs (and 80% of projected new technical jobs)—risk going unfilled at current degree completion rates. Of the unfilled jobs, 39% will be technicians, most of whom will have certificates or two-year degrees; 35% will be engineers with four-year degrees or computer scientists; and 26% will be engineers at the master’s or PhD level (Link).

While these projections might be valid, they are based on many assumptions that might play out differently than intended. The US policy of reshoring depends on subsidies and immigrant visas, which is not the favourite topic of the incoming US administration. TSMC has also found that more than the US labour force is needed to run an advanced fab, and the Taiwanese giant has made several immigrant islands inside the US.

Undoubtedly, the long-term semiconductor market calls for more talent and likely better-educated talent. Before that, there is the current semiconductor upcycle to worry about and a potential supercycle in 2025 (The Immense Changes in the Semiconductor Industry).

In this article, I will uncover the current situation from an employer's perspective and share the insights I have gathered.

Cycle economics

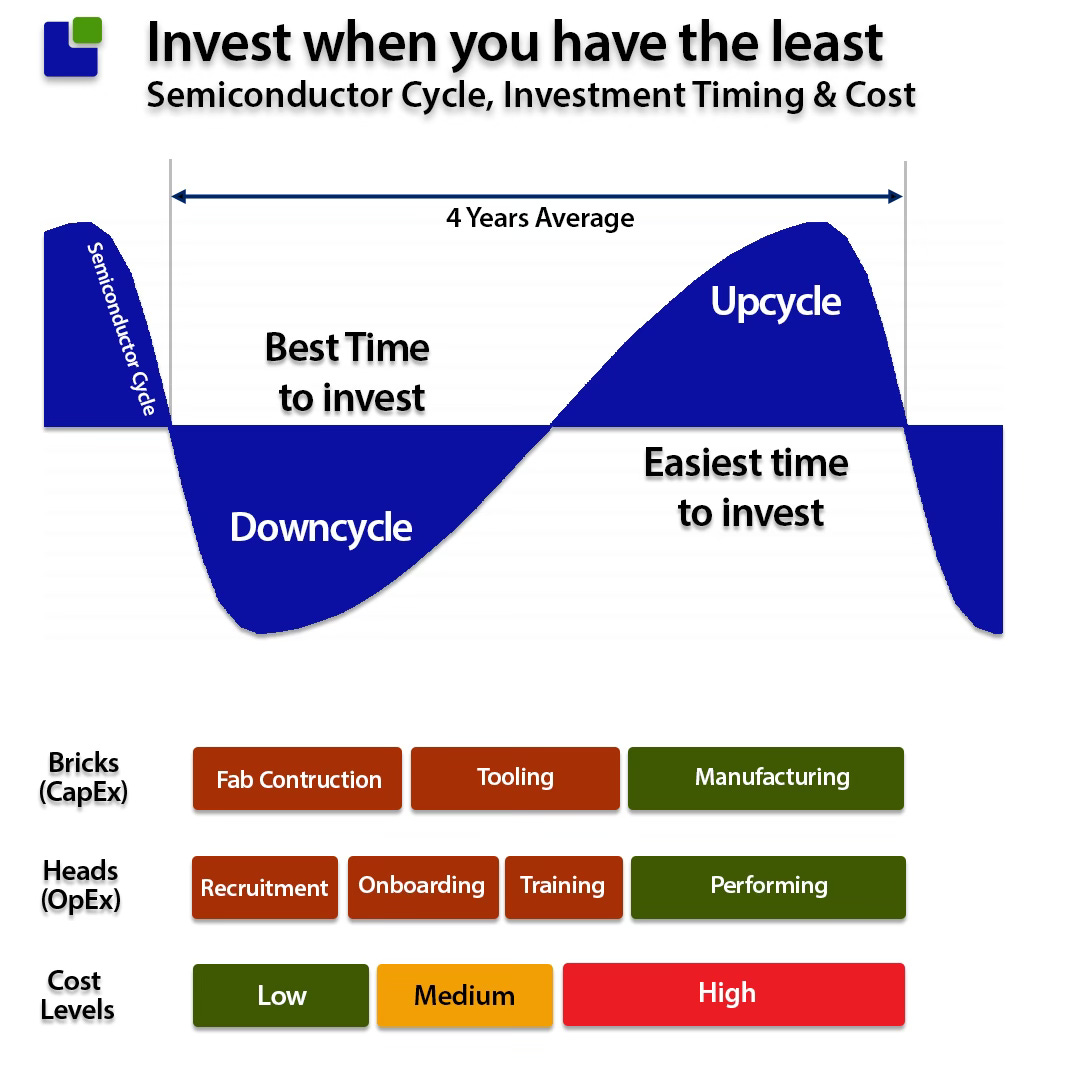

One of the characteristics of the Semiconductor industry is the semiconductor cycle of solid upturns and sharp downturns. The cycle is created by the dance between demand and supply that never synchronises, as the best time to invest is when you have the least resources.

So when your CEO is screaming about the closing quarter, you must remind the boss that now is the time to invest, as this will be the cheapest. There will be little competition for resources.

This is particularly important with recruitment as many positions require technical skills, industry knowledge, and adjustment to how things are done here. The job does not end with getting a butt in the seat.

You cannot have highly knowledgeable employees without attrition, so recruitment is a long-term game. That said, there are optimum times to press the accelerator and times when you should only reduce the activity to vital replacements.

The current market situation

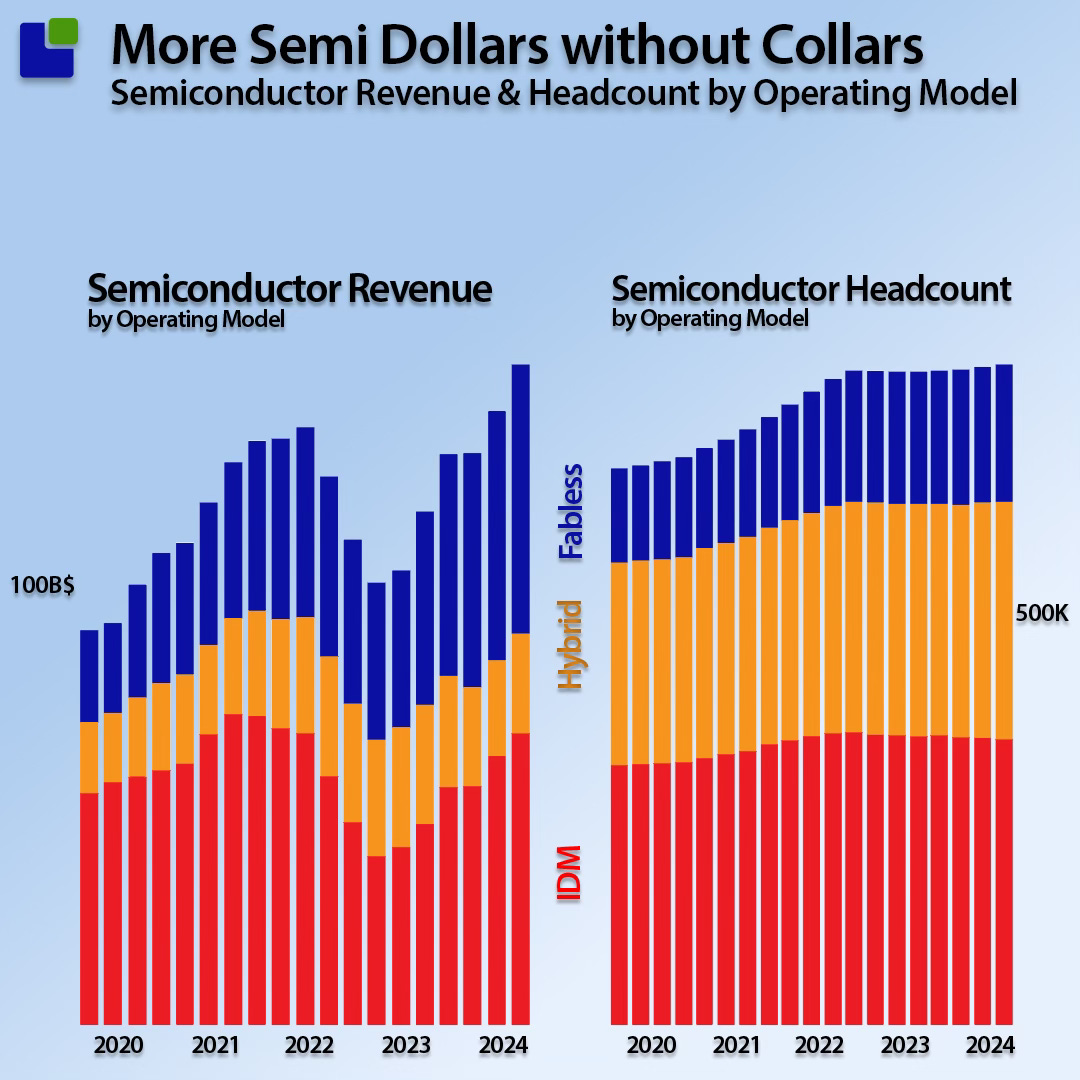

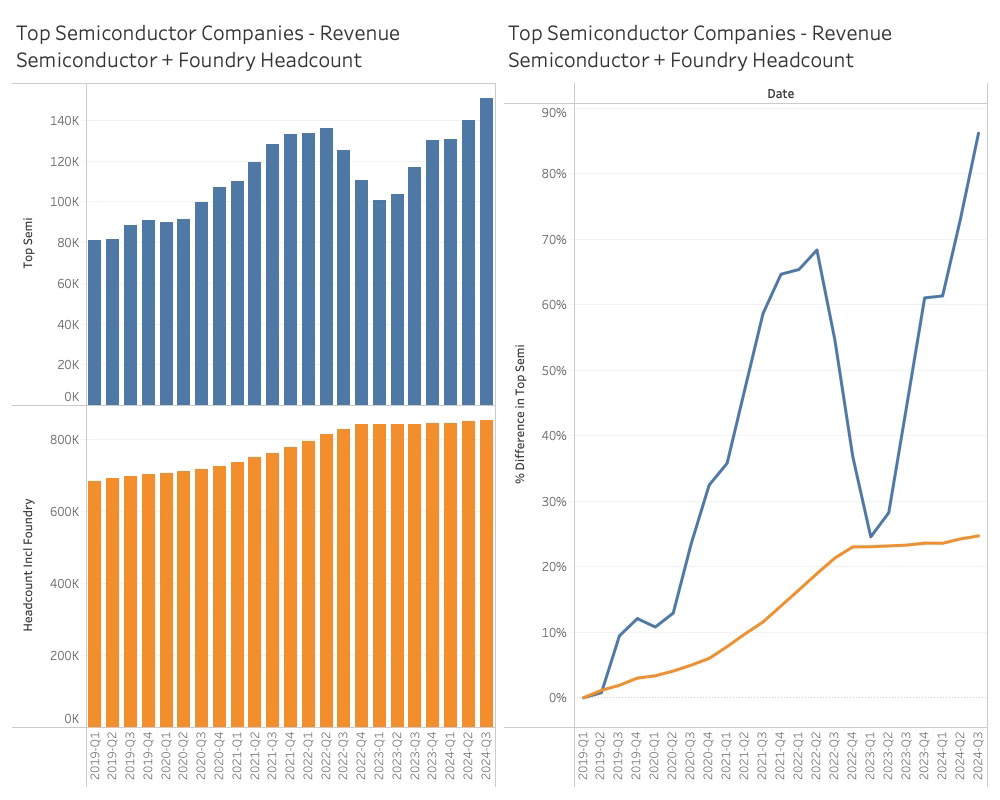

Rather than using WSTS, I use a more detailed dataset with named companies. The difference is about 10% to the WSTS numbers, but they both follow a similar trend.

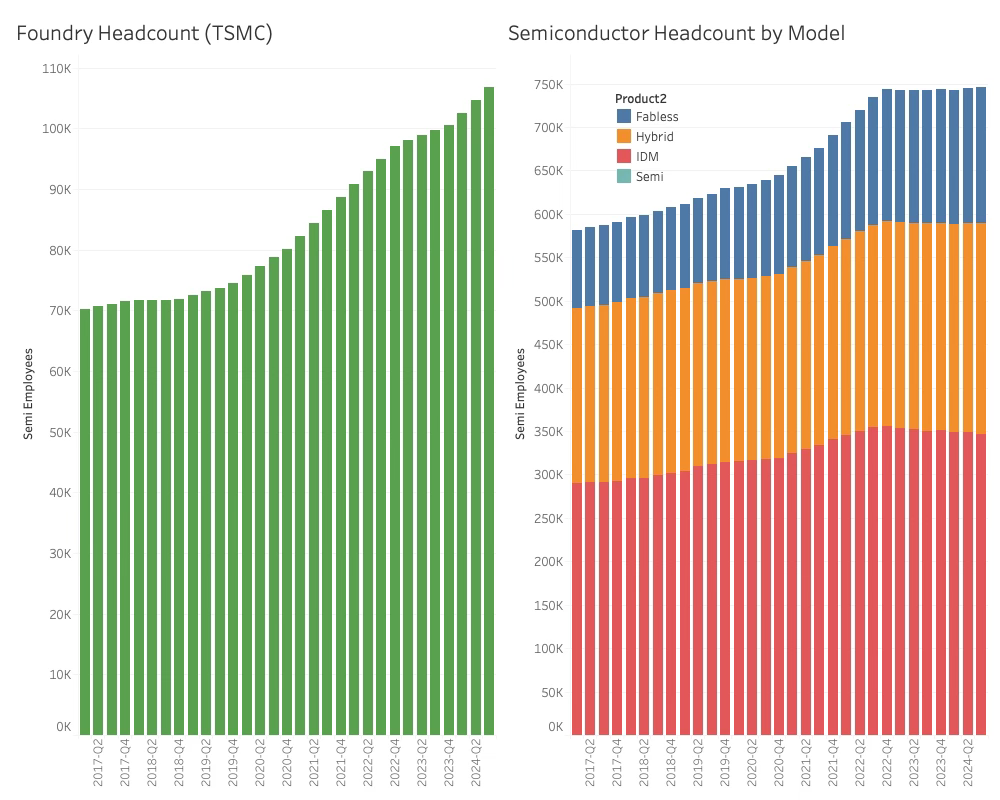

WSTS and the overall numbers suggest that the industry is far into a solid upcycle. However, the total industry headcount (we include foundry into the headcount to level the difference between companies with manufacturing and without) has levelled off. It has yet to grow meaningfully since the end of 2022.

There should be a battle for talent, but the semiconductor companies are not hiring or cannot get the people they need. As will be seen later when investigating the development in recruitment pay levels, the issue is that semiconductor companies are only hiring to cover attrition rates.

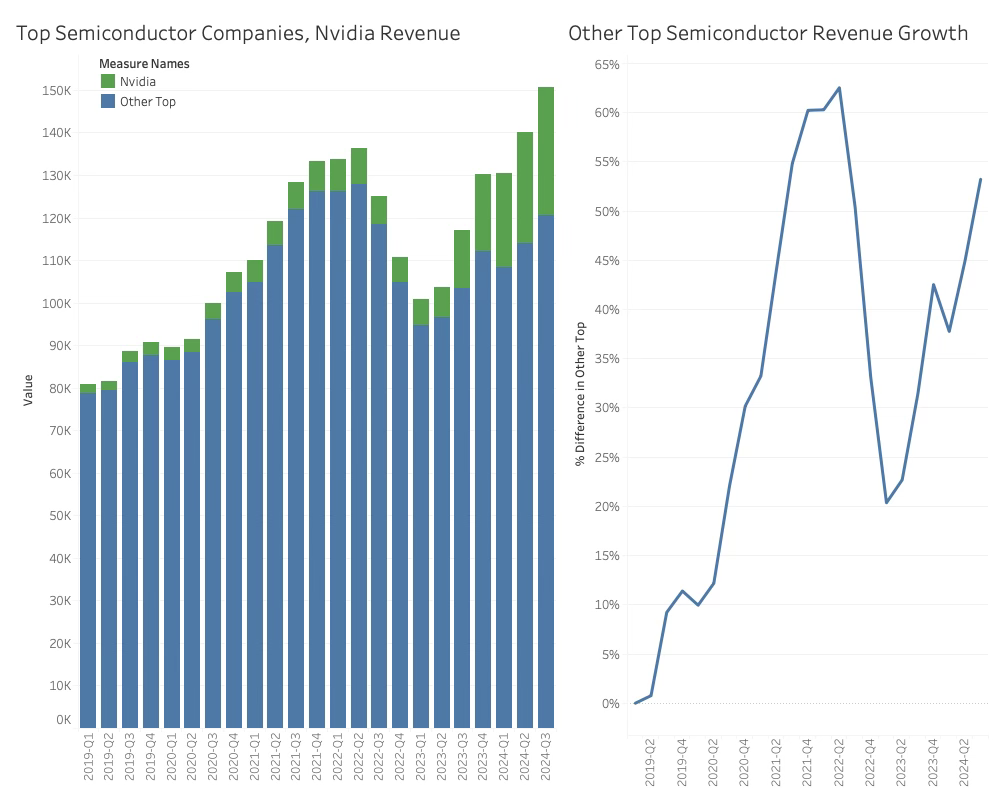

One main reason for this unique development is that this semiconductor cycle upturn differs significantly from other cycles in that a single company dominates it.

Without Nvidia, the overall semiconductor growth rate from the beginning of 2019 would have dropped from 85% to below 55%.

While Nvidia dominates the industry's revenue and operating profits, they do not meaningfully impact the headcount.

Nvidia made its big bet many moons ago and has been on a steady trajectory ever since. It now has over 30K employees and adds approximately 900 new employees every quarter. However, more is needed to impact the industry meaningfully.

A more detailed look into the industry headcount reveals the dynamics between the foundry market and the semiconductor companies.

As the Semiconductor headcount is a mix of fabless, hybrid manufacturing, and IDMs, there are varying degrees of manufacturing employees. What is apparent is that manufacturing is still moving from Semiconductor companies to foundry companies. This headcount increase is happening in Taiwan, the US, and, to a lesser degree, the EU and Japan.

A significant reason for this development is Intel's demise. In 2024, Intel will lose 12K employees and suffer the humiliation of having to get 30% of its wafers produced by TSMC. The Intel headcount cut only represents around 1.5% of the employees of the top companies and should not be sufficient to create the flatlining.

The hybrid and fabless companies are still adding employees, but not sufficient to offset the bleeding of the IDMs

It will be interesting to follow the future headcount. A lot of capacity is coming online in Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and the US, while a looming downcycle in late 2025 could limit growth.

The boundary condition is that the industry's headcount is only growing slightly, which should favour employers.

Semiconductor Employee Trends

Although the number of employees is stable, people still move between companies. There is constant churn as the best employees receive offers, which they weigh against their current package and option schedule.

While pay attracts employees, there are other factors in their retention. According to McKinsey, work environment and career development opportunities are the top issues in retaining Semiconductor employees. They also state that in 2023, 53% of employees considered leaving their jobs, up from 40% in 2021.

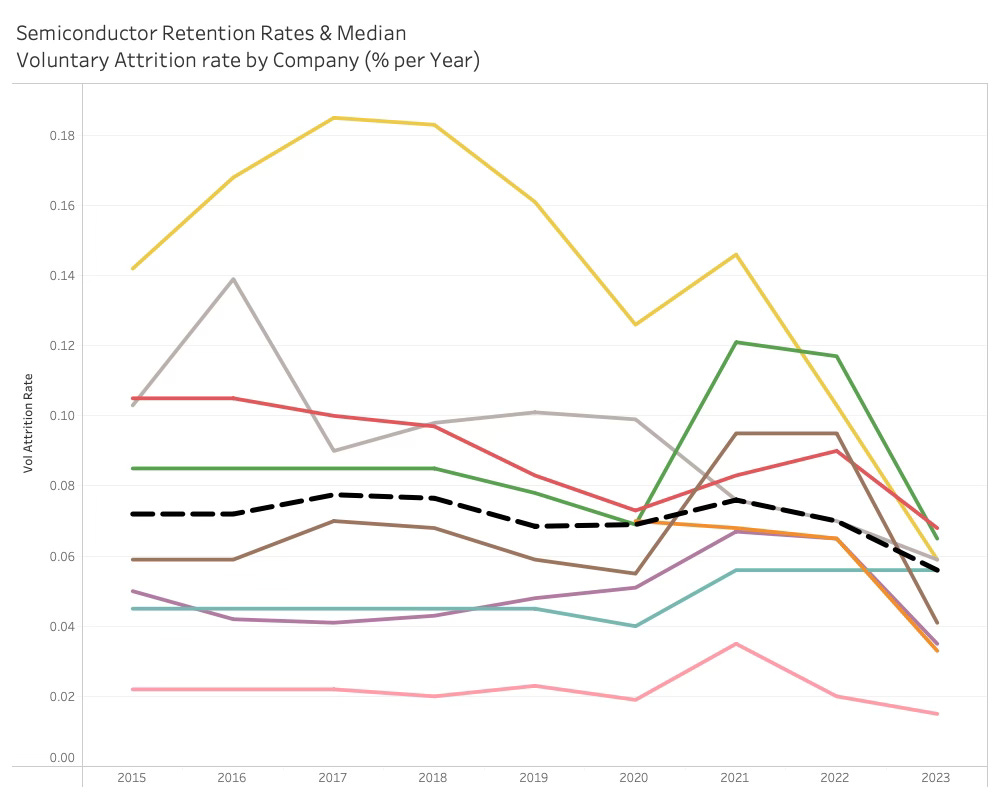

The following employee data is based on several large semiconductor companies, identified by individual lines and colours.

The first and most crucial employee ratio in the Semiconductor industry is the voluntary attrition rate, or the share of employees who terminate their jobs in a year. This does not include terminations by the company.

There is a clear downward trend in the attrition rate, although there is a significant difference from company to company. Some of these are company-specific, others are due to regional differences.