Should somebody have cried Wolf?

Tik, Tok, Tik Tok, SIC SUCK. The end of Wolfspeeds massive bet.

Rumours are circulating about a potential Wolfspeed bankruptcy and its potential impact on the Silicon Carbide market. While I will address this topic later, this post will focus on Wolfspeed's business and the effect of the massive bet the company made on the SIC market.

While it is easy to praise the winners and alienate the losers, both outcomes usually start with a big bet. In the Semiconductor industry, you will fade to irrelevance without a big bet and eventually end up in one of the M&A factories.

I have the most tremendous respect for the big bet, irrespective of the outcome, and it is in that light that I set out to investigate the financials of Wolfspeed. It is no secret that I have been unable to reconcile the Wolfspeed numbers with common sense for quite some time, and this has only worsened.

We are likely far beyond salvation for the entity known as Wolfspeed Inc., but the company's assets are likely to survive in one form or another.

Although Wolfspeed is unique in many ways, I will make comparisons to semiconductor companies that employ the hybrid manufacturing model, as their business model is the closest.

My readers will know that it is a speciality of mine. I love comparing pears to apples, although I'm told that I shouldn’t. You can always compare the financials of two companies, irrespective of the sector they are in. That is one of the purposes of corporate finance: To understand if one company or another is a better investment.

As long as you understand the context, you can compare anything (and it is called fruit by the way).

Wolfspeed's corporate roots date back to 1987. It was incorporated on a sunny day in Delaware and given the proper name Cree Inc. While the background for its name has never been revealed, it could be referring to a Native American tribe, which rightfully could be using the Reagan slogan of "Making America great again”

From the beginning, Cree was a materials science company pioneering Silicon Carbide for LED manufacturing. Over time, it became known for breakthroughs in blue LEDs, high-efficiency lighting, power and RF semiconductors.

In 2017, Greg Lowe took over as CEO, and with him, the company began a new strategic direction. While it is common in this industry and others to assign all success and failure to a single individual (to justify lavish pay packages), I don’t subscribe to the hero leader myth. Indeed, the CEO (usually) has the most power; the CEO is more like the mother crystal that initiates further crystal growth.

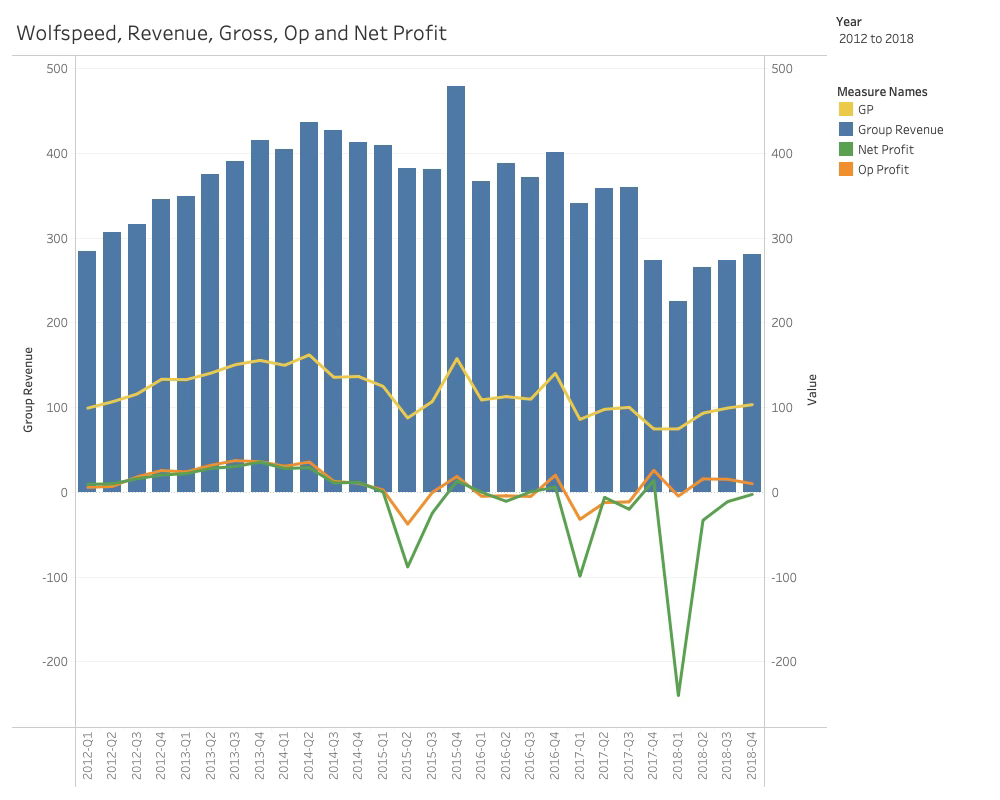

The company was not in bad shape, although it was not showing any growth either.

A strategic review of customer forecasts, conducted at a time when Cree was capacity-limited, suggested that it was time for capacity expansion. The plan involved doubling the SIC capacity while also increasing capacity for power and RF devices.

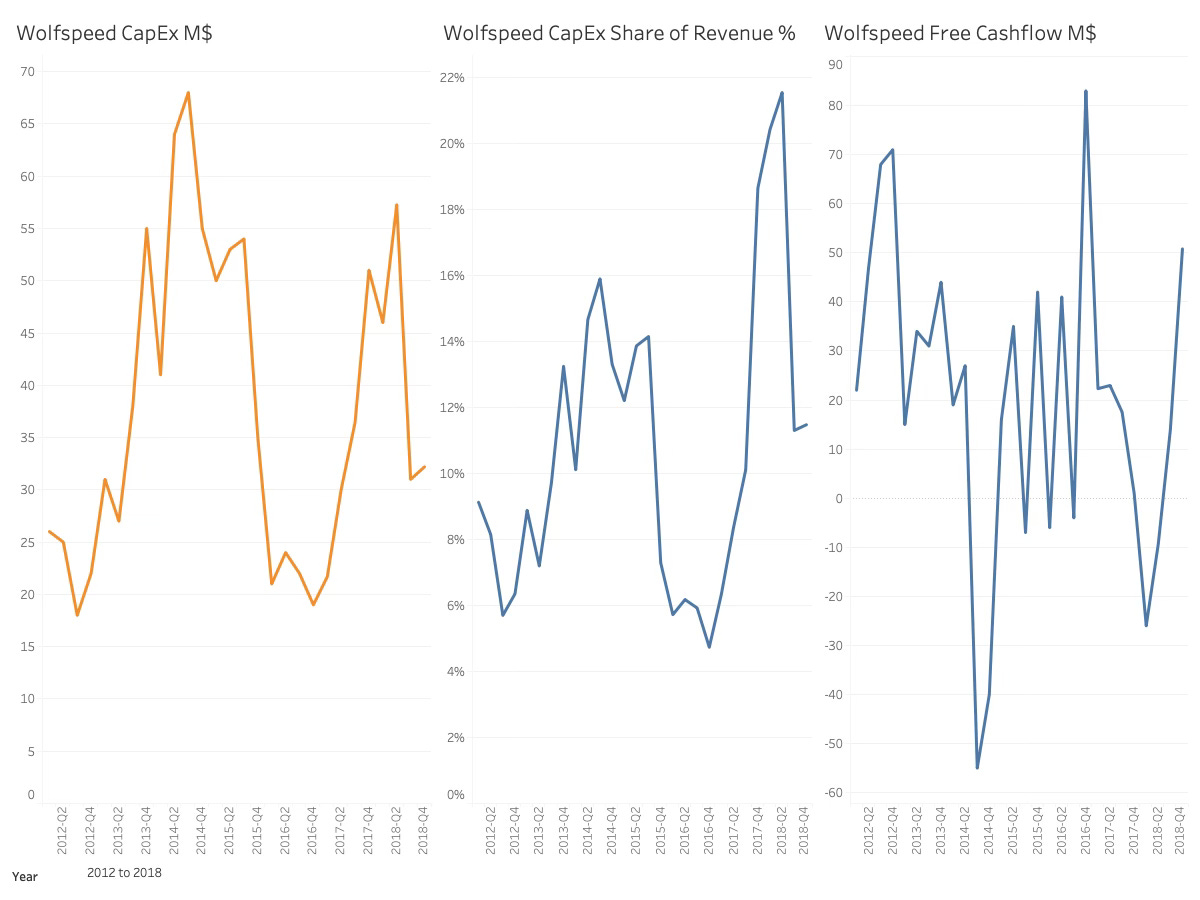

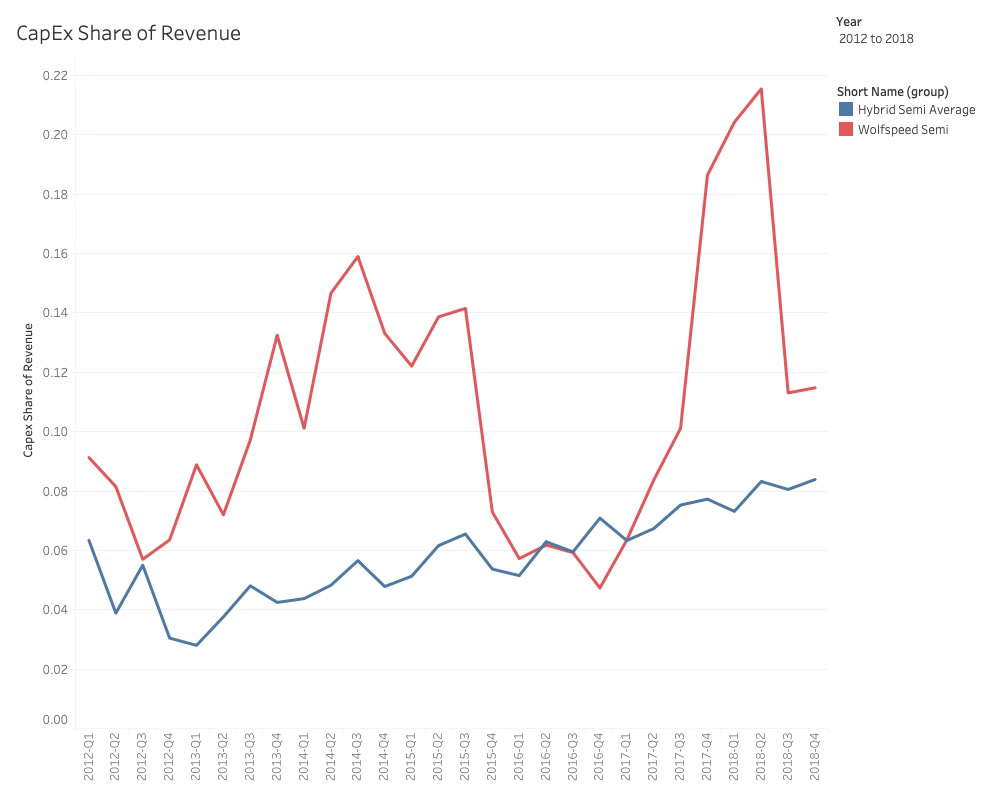

The company would significantly increase capital expenditures (CapEx) in 2018, accepting a negative free cash flow to fund the expansion of its capacity.

The CapEx investment for 2018 peaked at $ 57 M, representing 21% of revenue, and Cree returned to positive free cash flow in Q4 2018.

Comparing Cree to the average of hybrid semiconductors showed that the investment initially brought the company above the average of its hybrid counterparts. Still, it returned to being in line with the average by the end of 2018.

During the year, the LED business, which had been experiencing weakness, was realigned to target applications with higher profitability, and the RF of Infineon was acquired.

In 2018, the realignment of the LED business hurt revenue; however, operating profits returned to a higher level than before the strategic action.

After shredding some non-core assets and depreciating assets of the lighting business, the CapEx investments brought Cree’s Property, Plant and Equipment to 675 M, a new peak.

While Cree had lower revenue, the business was realigned towards more profitable segments and applications, and things began to point in the right direction.

This could have been a time for the long-haul optimisation of the realigned business to make it profitable and sustainable, but Cree had more ambitious plans.

The Power/RF business had been growing at over 90% year-over-year, and there was a project funnel of over $1 billion.

This is where the wheel starts to fall off the cart. In semiconductor companies, you spend several quarters designing a product, then you introduce it to customers, and after another few quarters, you start to sell. To manage the business, you keep a meticulous collection of opinions in Salesforce, which you eventually consider firm data.

The most honest salespeople only lie a little bit about their project value, but they base their information on what their customer tells them.

If you give a customer a better price for higher volumes, you also invite your customer to lie about their volumes (don’t you look so surprised!). It is also well known that customers run projects in parallel as a precaution, in case something goes wrong. Lastly, in times of scarcity, many projects are run in parallel to secure supply.

While there is a causal connection between the funnel value and the future revenue, the semiconductor leaders believe in the fallacy that it is a simple proportional relationship, and you can calculate your future revenue.

Once this lie has entered the corner office, there is pressure on the salespeople to increase the funnel (easy as selling rubber bands by the yard).

Based on the positive growth of the RF/Power business and the value of the funnel, a new investment plan was made. Over the next 24 months, capacity would double again. Not only was it based on the increasing revenues of the Power/RF Devices, but also a play into the materials business.

Shortly after, the Lighting division was sold, and the transition from LED to Power/RF/Materials, which was previously under the divisional name of Wolfspeed, began. The transformation was completed with the sale of the LED division in 2021.

Wolfspeed was now an end-to-end semiconductor company with a few additional products.

Investments in Wolfspeed's capacity expansion continued, with planned capital expenditures (CapEx) of around $200 million in fiscal 2020 and $400 million in fiscal 2021 (later increased to $550 million). Fiscal 2021 was described as the peak investment year for long-term growth.

Construction began on the Mohawk Valley Fab, a new facility intended to start ramping production in calendar year 2022. It was designed as the world's first fully automated 200mm silicon carbide fab. The decision was made to go directly to 200mm from the start in Mohawk Valley to save qualification cycles and accelerate adoption.

Expansion of the Durham fab and materials factory was also planned, including expanding materials operations to a second building to increase capacity by 30x.

Wolfspeed signed multiple long-term agreements for silicon carbide materials and devices, valued at over $500 million in aggregate by Q3 fiscal 2019. These agreements generally included upfront customer deposits to secure purchase obligations and capacity, with pricing aligned with the company's long-term margin goals. The strategy focused on long-term relationships rather than the spot market.

If this were a fairytale, the story ended here, but things were about to change.