The Corporate Sandwich Model

What is the filler in Intels sandwich?

If you have spent time in corporate, you likely received performance feedback (criticism) using the sandwich model. This is an HR response to people being offended by receiving direct feedback from their manager, often after missing a target. The first attempt at redefining a bollocking was to rename it to (highly uncomfortable) coaching - but employees saw through this.

The next step was to create the Sandwich model of feedback. The sandwich feedback model gained popularity in the 1980s, largely attributed to Mary Kay Ash, the founder of Mary Kay Cosmetics. She advocated for this method, advising managers to cushion critical remarks between layers of praise to maintain morale and encourage improvement.

This method involves “sandwiching” the critical feedback between two positive remarks:

1. Positive Feedback: Begin with a genuine compliment to set a positive tone.

2. Constructive Criticism: Introduce the area needing improvement.

3. Positive Feedback: Conclude with another positive comment to end on an encouraging note.

A cynic (who, me?) would say that the filler defines the sandwich. A shit sandwich is still a shit sandwich even if you use nice bread, but I will let people have their own opinion.

From a feedback model, it has gained popularity in other areas of corporate, including corporate communications. Start corporate communication with positives, slip in the problematic information in the middle, and end on a high note.

While Western companies mainly use this model, it is also deployed in the East. More subtly, however.

With the Chinese being the most direct and the Japanese being the least, you can be sure there is a problem if you encounter two pieces of bread.

Being of Viking descent, I struggle slightly with feedback models as we use somewhat more direct feedback (“Stop bleeding and pick up your battleaxe!”), but I understand the concept when I see it.

The Intel Sandwich

We knew that Intel had a busy quarter with mid-quarter strategy updates (Sign of the Timing), which I believed signalled serious problems with meeting the quarter guidance.

While I like to be right as much as the average bloke, it should not get in the way of facts. Where I was wrong was concerning revenue. I did not believe Intel could meet guidance, but they did.

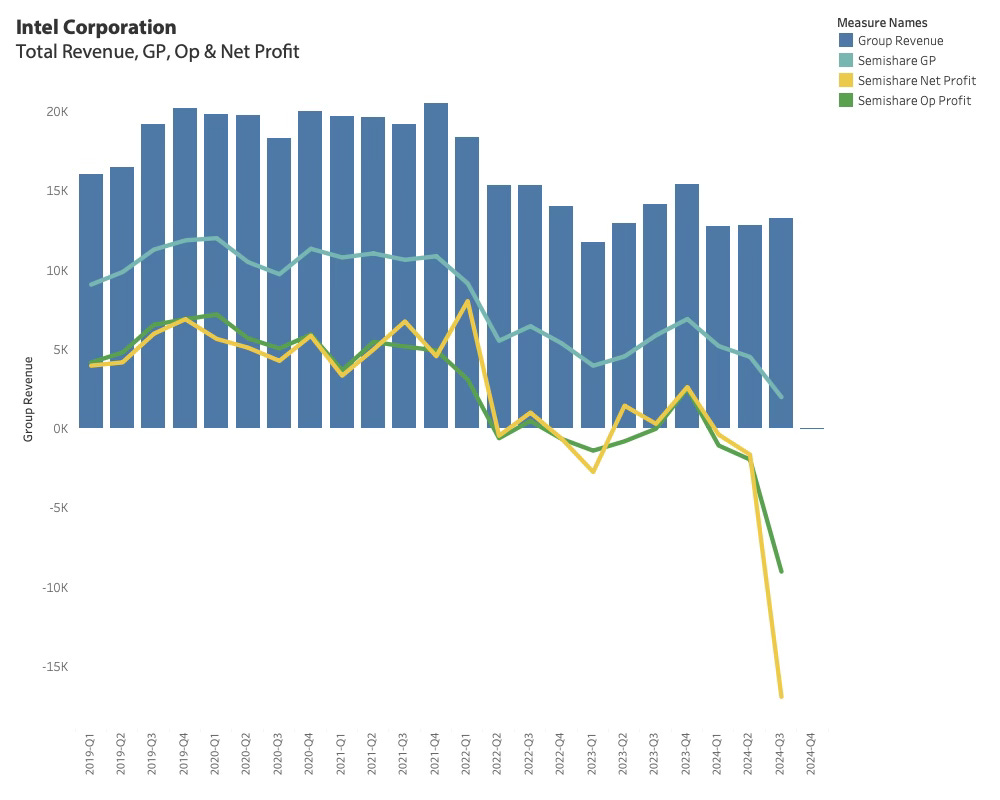

Where I was right was concerning profits. Intel guided 34.5% GAAP gross margin but delivered 15% - this is not a near miss; it is entirely off the radar.

Rather than delivering $4.6 billion, the business delivered less than $2 billion. As Warren Buffett states, “A billion here and a billion there, and soon you are talking real money.”

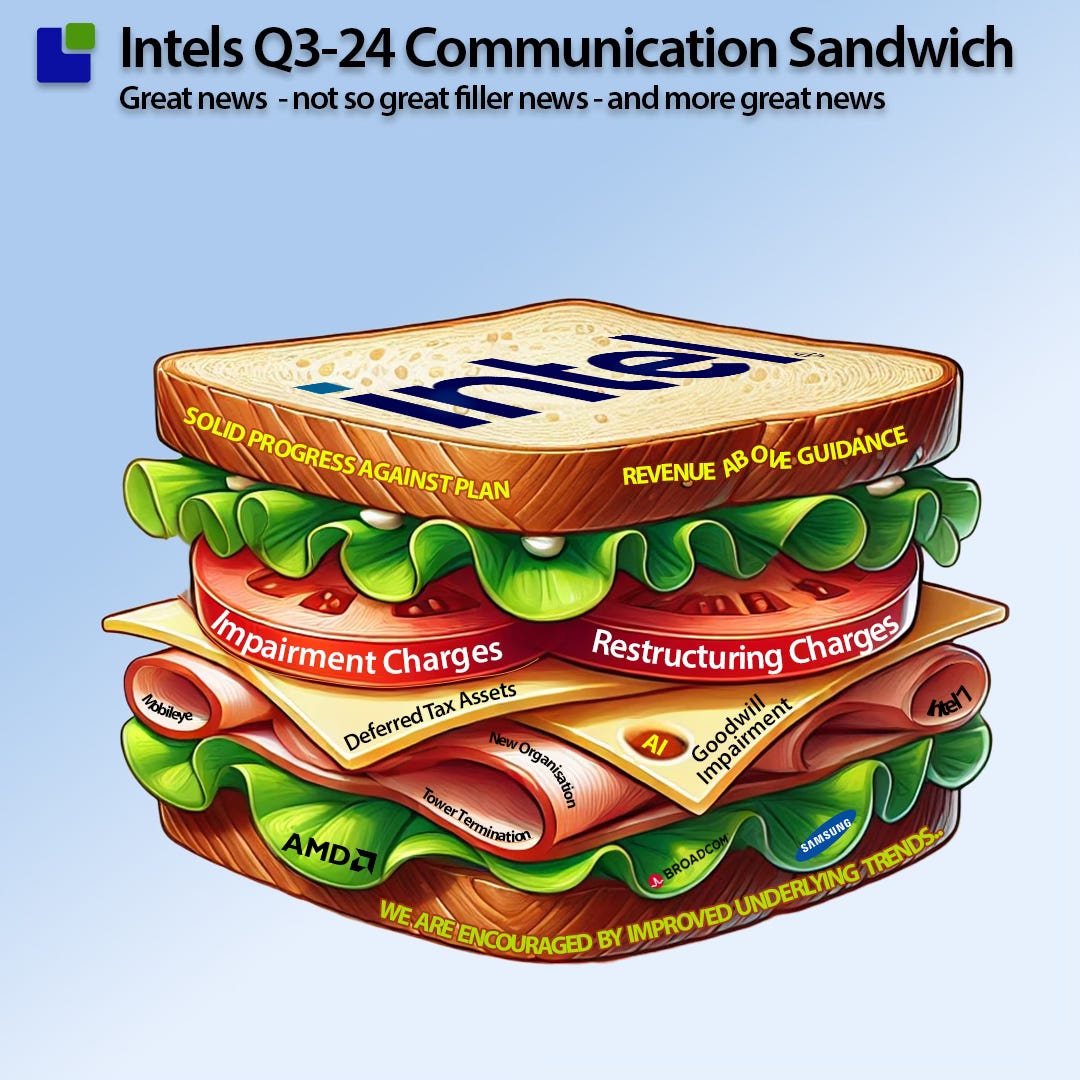

As Intel called Q2 performance disappointing, they must have invented a new word for Q3-24 performance. But no such thing. The corporate sandwich was served as

“Our Q3 results underscore the solid progress we are making…”

“Restructuring charges meaningfully impacted Q3 profitability…”

“We are encouraged by improved underlying trends….

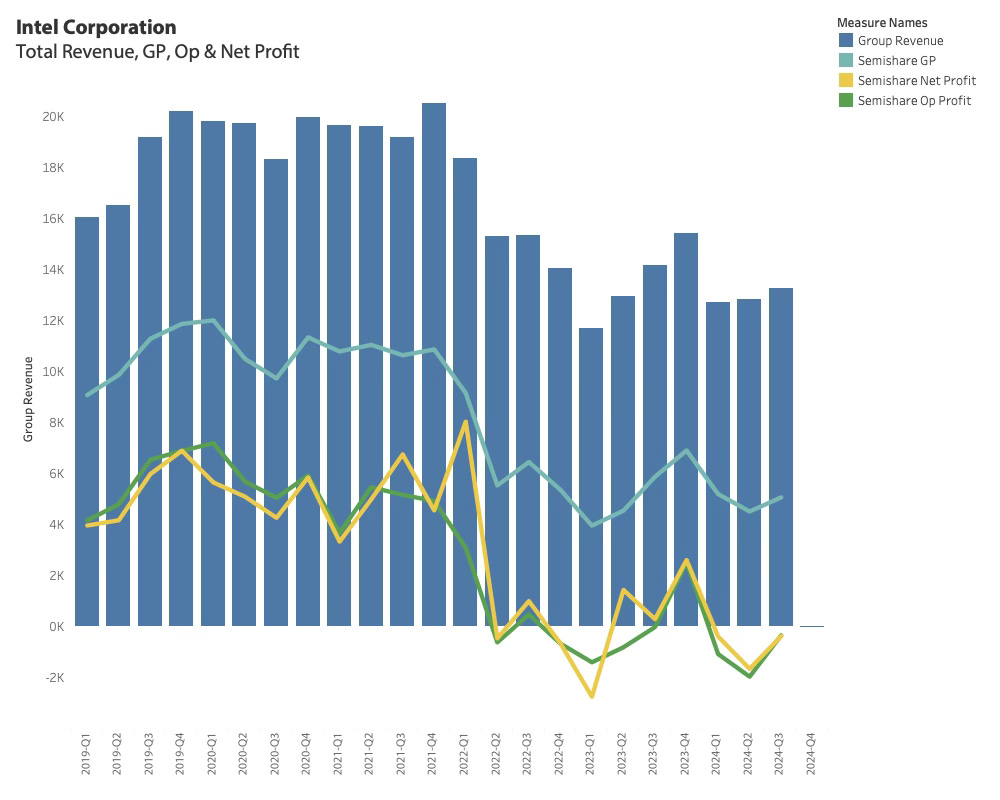

GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) is there for a reason. It ensures management follows a fixed set of rules to report their numbers and make companies comparable. Non-GAP numbers are often also included, and while their calculations might be proper, they are still not GAAP. All of the Intel charges are according to GAAP, but if we exclude them, the Intel result would look like this:

This looks much better than the GAAP view and gives us insights into whether Intel’s business has turned a corner. So what are we to believe?

It is time to dig into the financials using my “The Butcher Book of Corporate Finance and Accounting”. While my finance and accountant friends roll their eyes at my Corporate Finance skill set, it usually works within a brick or two at the strategic level.

What the hell does this mean?

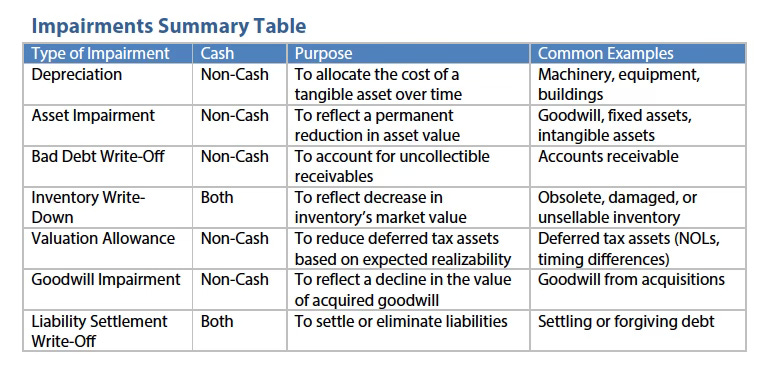

While restructuring charges involve expenses and cash paid to employees and others, the impairment charges are mostly cash-less exercises.

This means no cash flows in or out of the company due to these charges. The most common impairment charge is depreciation. It allows the cost of a tangible asset like a semiconductor fab to be allocated over time in a way that tracks the useful life of the equipment.

Depreciation does not involve cash, as the fixed asset is paid upfront, but as depreciation is recorded as an expense, it reduces the taxable income. It allows companies to deduct the CapEx cost over the useful life of an asset more in line with the tempo at which an asset generates income rather than when the investment was made.

Depreciation impacts the balance sheet, reducing the position of equipment, property, and plant in factories or machinery.

Like depreciation, most other impairment charges do not involve cash. Below is an overview of the most common impairment charges.

Intel recorded three different impairment charges apart from the restructuring charge.

A valuation allowance of 9.9B$.

A deferred tax asset is an accounting term for a situation where a company has paid more taxes than it owes in a given period, creating a benefit that it can use to reduce future tax payments. Essentially, it’s a tax-related asset on a company’s balance sheet that reflects overpayment or a timing difference that will be favourable for the company’s tax liability in the future. Intel’s case also involves tax benefits from the Chips Act funding (A Billion here and a Billion there).

It is a non-cash exercise that reduces Intel's book value by lowering the non-current asset on the balance sheet. While cash is not involved, Intel is now worth less from a book perspective.

The charge implies that Intel does not believe it will make sufficient profits to deduct from. Despite the positive attitude of the investor communication, his represents a more pessimistic view than a quarter ago.

A goodwill impairment of 2.9B$

The simplest explanation of Goodwill is that it enters a company’s books when an acquisition is made. Especially in tech, there is a significant difference between a company's book value and what it is worth.

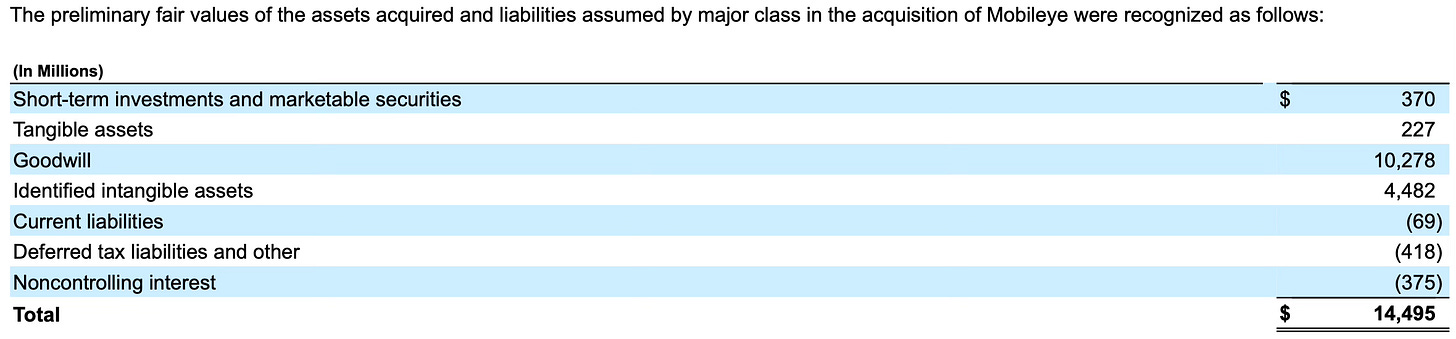

The Goodwill impairment charge was related to Mobileye. The calculation for the Mobileye acquisition in 2017 can be seen below.

Out of the 15B$ acquisition, more than 10B$ entered Intel’s balance as Goodwill to make the books balance. If Intel were to sell Mobileye for the same amount, the 10B$ would leave the balance sheet, but generally, the goodwill stays on the balance sheet.

Goodwill can change through an impairment charge, which occurs when the underlying asset's value is tested to be less than before. The valuation is complex but generally linked to the asset's ability to generate cash flow after being discounted.

In other words, Intel now believes Mobileye is worth less than last quarter, 2.9B$ less.

Again, this is a non-cash exercise that lowers the book value of Intel, but it is also a declaration that Mobileye's prospects are less promising.

An Asset impairment charge of 3.1B$

The asset impairment charge is an accelerated depreciation of Intel’s manufacturing assets related to the Intel 7 process.

The Intel 7 process was introduced in 2021 and is considered one of the reasons Intel is in a pickle now (Intels Mountain to Climb).

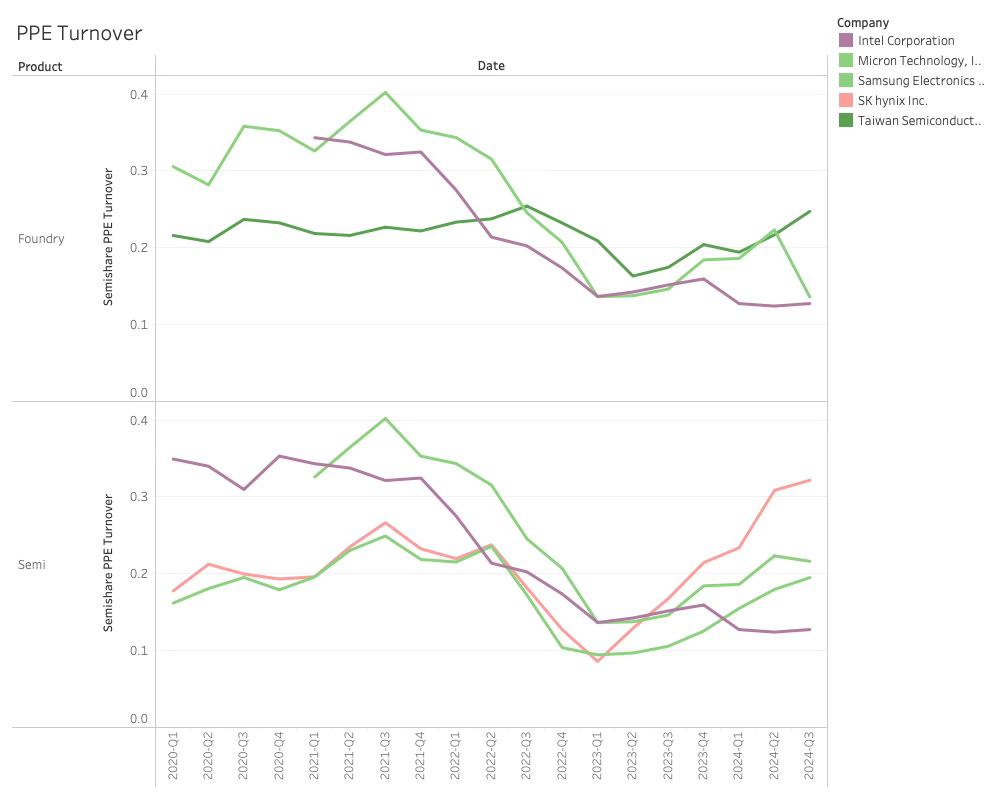

In 2021, Intel generated 0.35/qtr for every Property, Plant and Equipment dollar. Still, after the semiconductor cycle lows, the Intel PPE Turnover did not leave the teens area and is currently under $0.13/qtr. TSMC is at $0.25, and SK Hynix is at $0.32

In other words, Intel needs to generate better returns on PPE as the Intel 7 process is ineffective and most likely commercially worthless.

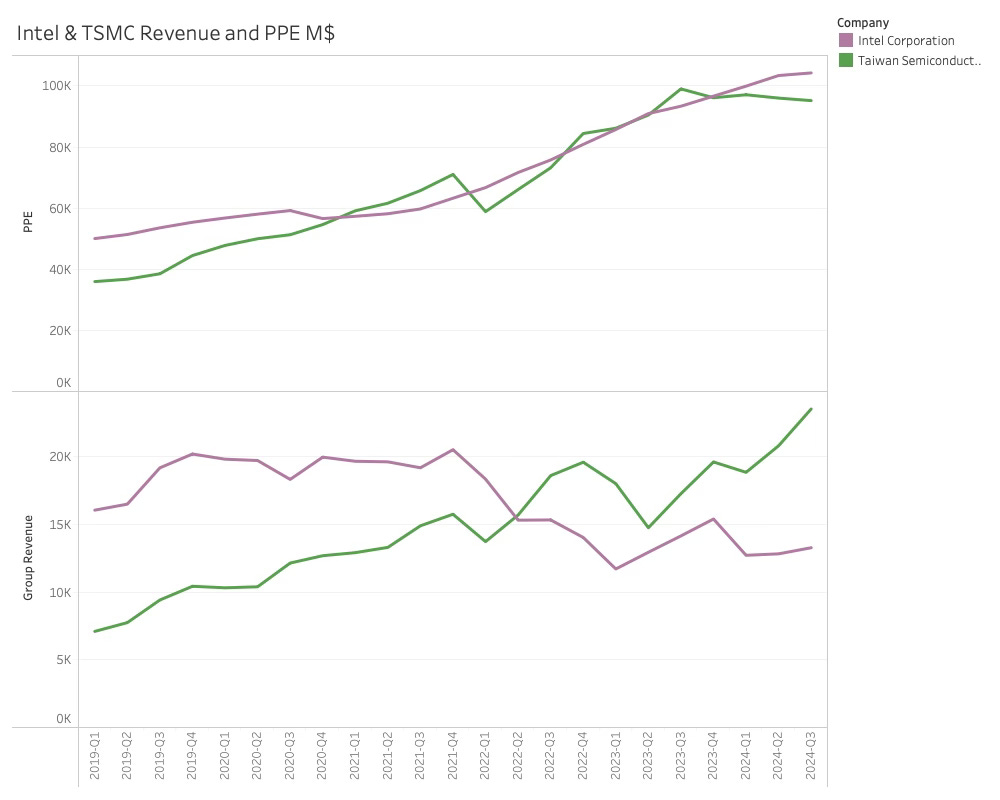

The impairment charge lowers PPE by 3.1B$, but PPE still increases as CapEx's spending exceeds the charge.

This can be seen below in the comparison with TSMC. While this is not an apples-to-apples comparison, it is still interesting to see the shift over time in what can be achieved with similar-sized PPE.