The Immense Changes in the Semiconductor Industry.

End of the Semiconductor cycle?

Many years ago, when I was a young lad and Jerry Sanders wore shorts, the Semiconductor industry was wonderfully simple. “Real men have Fabs”, as Jerry would say, and semiconductors were designed, produced and sold by the same company.

As the industry was interconnected, the markets started synchronising into a boom/investment cycle and a bust/frugal cycle. The overinvestment was followed by underinvestment, as the best time to invest was when you had the least amount of money.

Everybody reported their sales to the WSTS, and you could follow the ebb and flow of the industry. The semiconductor cycle was born.

We accepted this as a fact and did not speculate much about it. Things go up, and things go down in the semiconductor industry.

Having a background in sales organisations, we knew there was an upcycle where we had great products and a downcycle where salespeople could not sell. an upcycle where our CEO would begin, “Under my leadership, we have … and a downcycle where the CEO would state, ' It is the market, stupid.”

While most of my peers just accepted that the tide lifts all ships, I got very curious about the cycle and the intricate network of businesses that created the cycle.

This was important as everybody was investing and hiring at the same time as everybody else, driving costs through the roof. There must be a better and cheaper way of doing this if you understood the cycle.

So, rather than accepting the cycle, I wanted to understand the causal relationship between the companies and their larger supply chain. The idea of Semiconductor Business Intelligence was born.

After a while, I was able to untangle the relationships, and I could say to my self:

“Before something happens, something else happens.”

The industry was founded on the willingness and ability to make big long term bets, and they would show up in the data a long time before they came into full bloom.

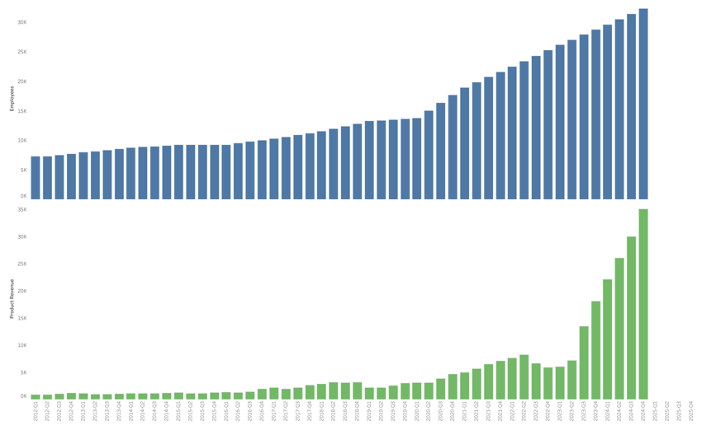

At the beginning of 2020, a graphics semiconductor company made a bet that would appear in their headcount. Three years later, Nvidia delivered its first AI-driven result, and the bet became visible.

While not all bets succeed, and they can be challenging to identify, the big bets are like bit cats; they leave prints and tracks wherever they move, and it is only a question of searching sufficiently hard.

Since I began, the industry has become immensely more complicated, while the semiconductor cycle remains the only constant. The latest WSTS numbers confirm this and show that we are now firmly into the upcycle of 2025.

However, much of my data showed a more complex story than an upturn. Something was different this time around.

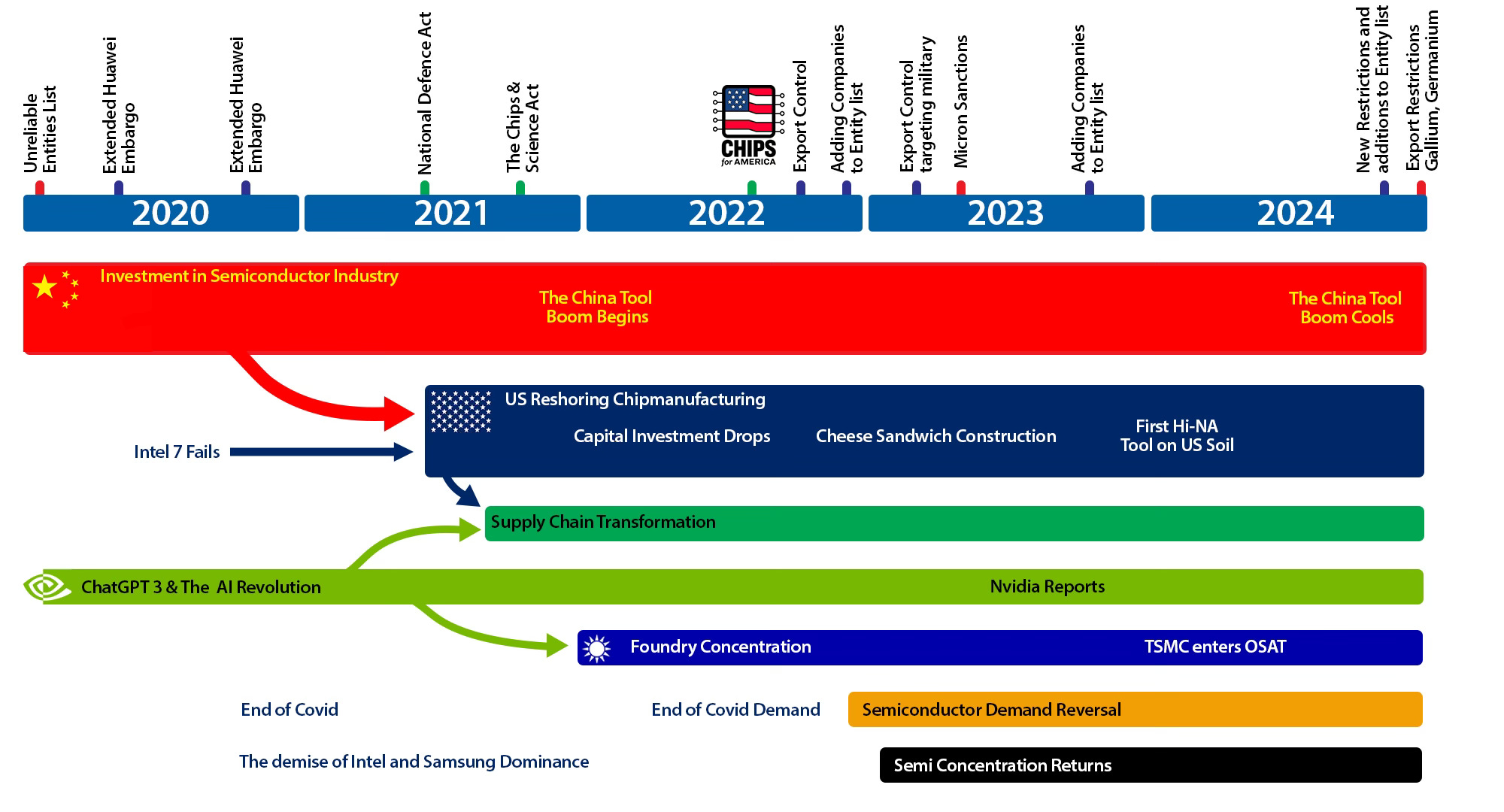

The Strategic Timeline

As the industry grew, it became global and sufficiently large to interact with the worldwide economy. It also increasingly became political and a matter of national interest and security.

The Chinese authorities were never satisfied by being the world's manufacturing centre. They knew the value was locked into Semiconductors and began a decades-long investment program aimed at self-sufficiency.

While the investments were huge, progress could have been faster, and the Chinese companies still relied heavily on Western semiconductor tools and Taiwanese manufacturing technology.

The US Semiconductor companies owned most of the Semiconductor revenue, but their focus was on the quarter rather than the decade, and outsourcing makes that game more straightforward to manage. Soon, the capacity had left the building.

Intel was left as the only leading US-edge manufacturer; the failure of Intel 7 in the mid-20s would turn pivotal for the industry. In an attempt to proceed without the expensive light show from ASML, Intel failed and exposed the vulnerability of the Semiconductor supply to the US military. Soon, there would be no leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing in the US.

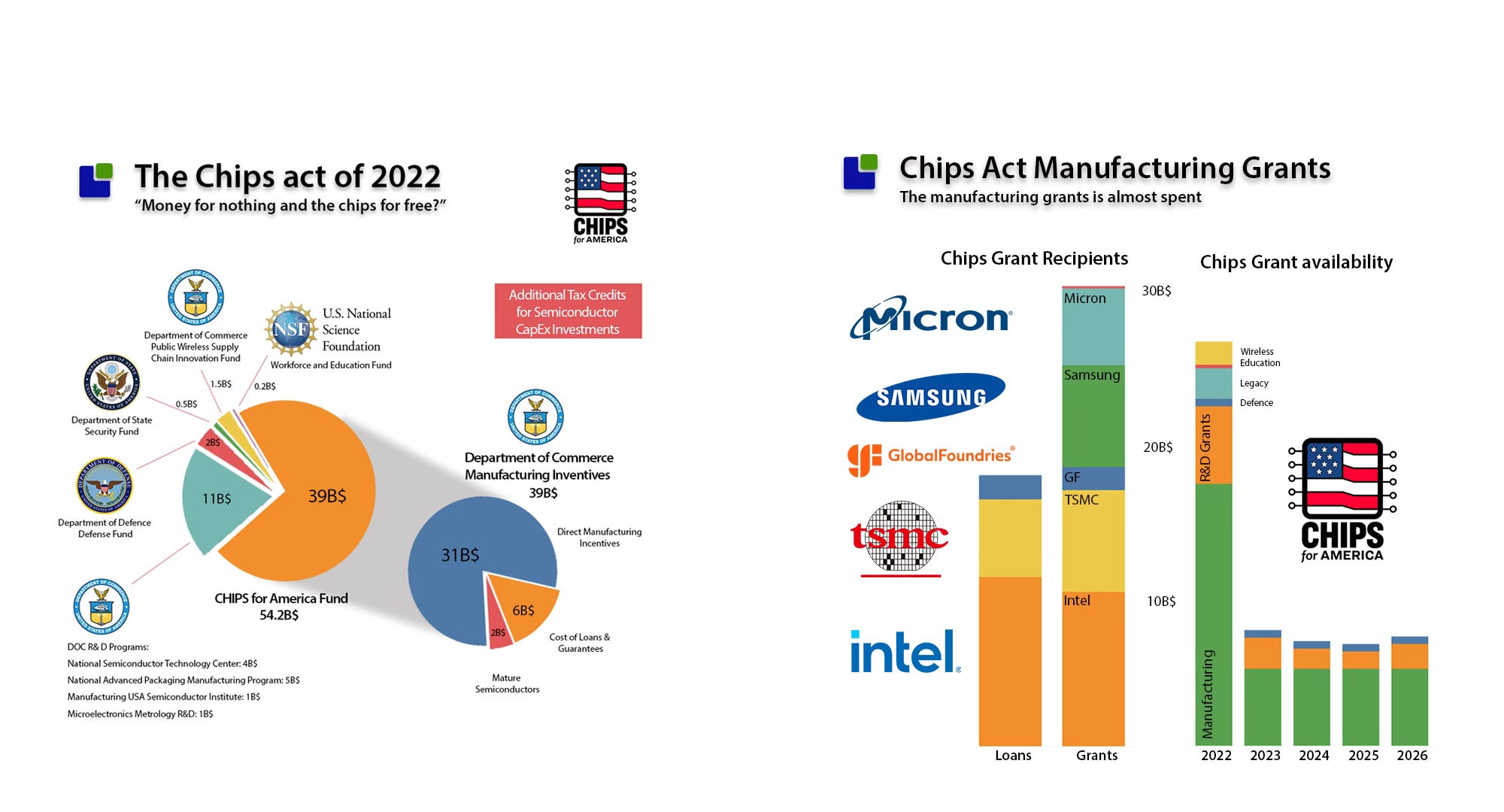

A year after, the National Defence Act was introduced with significant subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing. This would later become the Chips and Science Act, driving US reshoring activities.

Simultaneously, trade embargoes were emerging. There have been embargoes for deep UV tools since 2019, but they have had little effect. After the ratification of the Chips Act, gloves were introduced, and more draconian embargoes were developed.

This month has been especially busy with exchanges of embargo artillery between the US and China.

At the same time as Intel fails, the AI revolution is in its humble beginnings inside OpenAI and Nvidia. In late 22, ChatGPT was launched, and the AI revolution became visible. The scale became visible when Nvidia reported its first AI quarter one year later.

The AI revolution, combined with the embargos and subsidies, profoundly impacts the semiconductor supply chain, as we will show later.

From Economic to Political Drivers.

Economic factors, such as innovation, cost efficiency, and market demand, have historically driven the semiconductor industry. But now, decisions were increasingly shaped to address embargoes and to intercept chips act money.

The turn was sharp as the Chips Act money was significant and front-loaded.

While the US wasn’t alone in offering subsidies, the money was staggering.

Almost all of the subsidies were allocated within the first year, and all the major semiconductor manufacturing companies decided to participate and commit to fabs on US soil.

Intel likely was the direct cause of the Chips Act, demonstrated political savvy, and got a significant chunk of the subsidies.

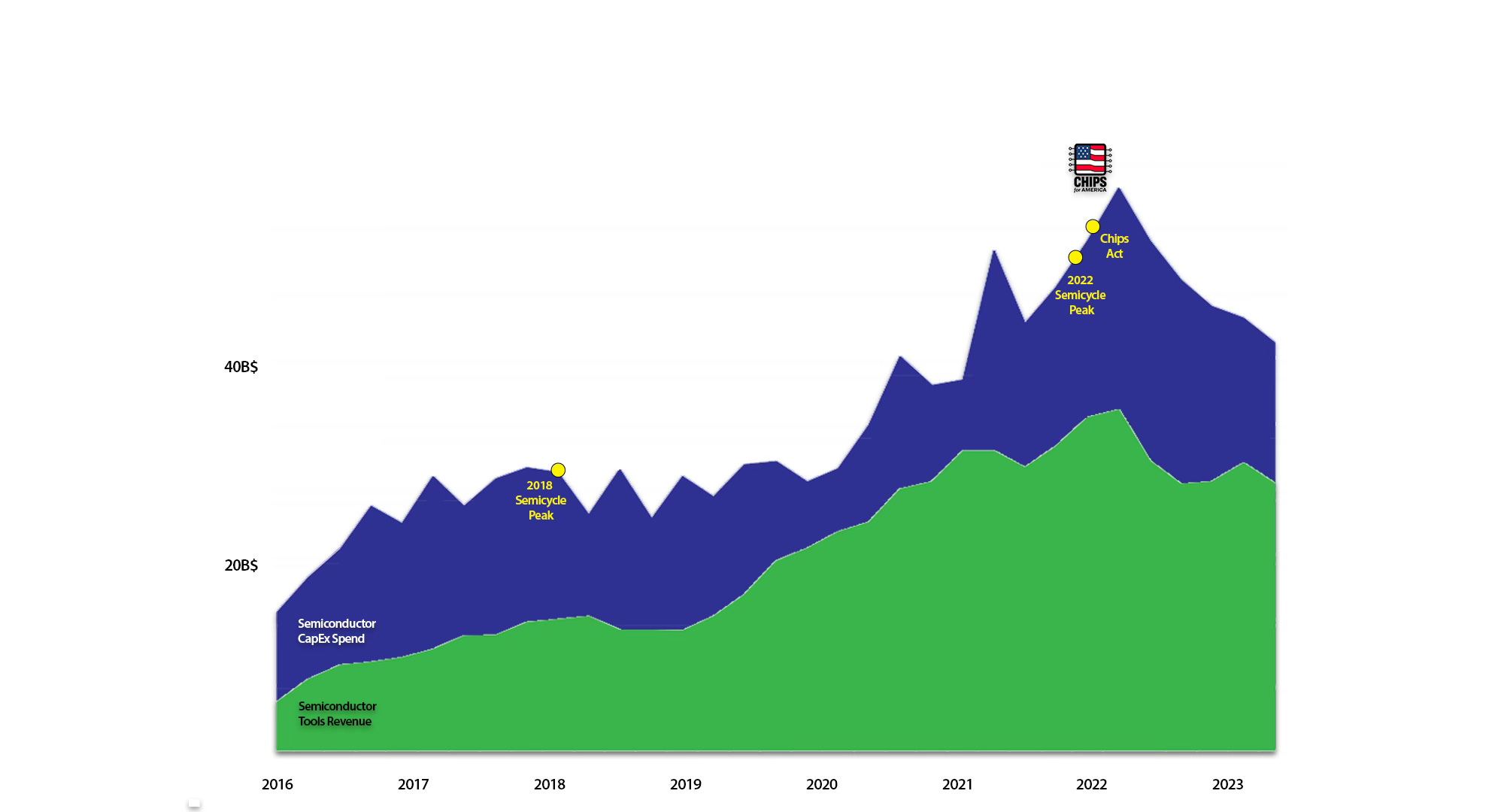

The subsidies immediately impacted the investment environment in the Semiconductor industry and disrupted the normal cyclical investment process.

Almost immediately after the Chips Act was ratified, the Capital Expenditure of the entire industry dropped significantly. While this was impacted by the end of the 22 peaks of the cycle, the drop represented the change in investment plans as a result of the Chips Act.

As the large semiconductor companies shifted to build new factories, the semiconductor tool sales were expected to drop significantly as new factories only needed tools after construction had happened. Surprisingly, tool sales stayed stronger than expected.

The embargoes and subsidies created a new tool demand in China.

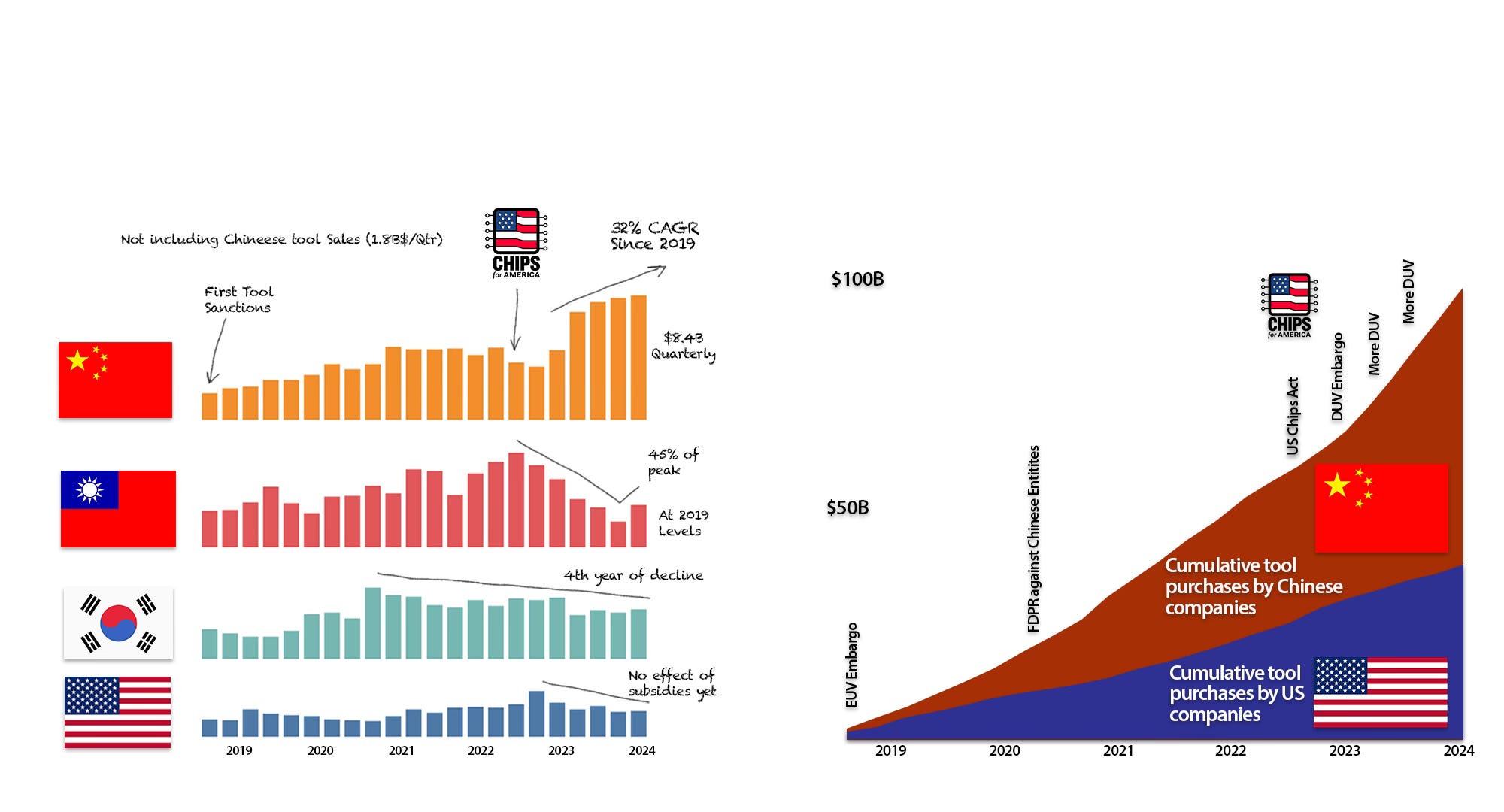

From a few B$ a quarter, Chinese tools consumption has grown to over 8B$ worth of Western tools and a couple of B$ of Chinese manufactured tools a quarter.

Since the first embargoes in 2019, the Chinese have significantly outgunned the US companies in cumulative tool sales. The level is still high but showing some signs of cooling.

The response from TSMC has been profound. After the Chips Act, TSMC tool purchases dropped by 45% and bottomed out at 2019 levels.

To nobody’s surprise, the US tool revenue shows no sign of activity yet as factories are being constructed.

The Reluctant Allied

As Intel discovered, there was only a commercially viable way to leading-edge nodes with the magical tools of the Dutch wizards in ASML.