The semiconductor industry is becoming mainstream and capturing headlines. When people hear that I work in it, it is not like it used to be (yawn, “sounds fascinating”, yawn). They want my opinion on Nvidia’s stock price and to understand the width of ASML’s moat. What do I think of the CSP’s investment levels, and is AI a hoax or tailing off? It is a lot nicer than being asked to fix their toaster.

While the AI revolution has been exciting, most people will survive just fine without an AI for everything. Living without the products of the Semiconductor workhorses is a different matter.

The Evolution of the Semiconductor Industry.

For non-insiders, the manufacturing models of the Semiconductor industry seem overly complex and difficult to understand. Back in the day (Real men have fabs), when the first semiconductor sprouts peeked out into the light, companies were manufacturing-based, and everybody huddled around the manufacturing equipment, trying to get a spot to work. When I was a young lad travelling to the headquarters, I was going to the Fab. I continued doing so many years after the fabs were outsourced or closed.

The Fab was fabulous, and so was the cost of staying in the Semiconductor manufacturing race. When the first pure-play foundries emerged, most semiconductor companies were relieved to eliminate the complex and expensive manufacturing process.

Many companies went fabless within a decade, while a few kept their fabs. These companies were typically involved in broader markets with many applications and customers. The customers also used various product technologies that did not scale as well as high-end digital did. Analog, Power, and RF are different games than digital, and it was less attractive to outsource if possible.

These companies also worked on applications that required components to be available over longer lifecycles. The life cycle of a high-end digital product and technology lasts around 18 months before new technology takes over. I don’t know about you, but I don't change my gas boiler as often as I change my iPhone.

While these companies kept their fabs, they could not manufacture high-end digital needed for their computational devices, particularly microcontrollers.

The Fab-Lite (Hybrid Manufacturing) model was born.

Hybrid Manufacturing

The companies incorporated the fabless/foundry model alongside the traditional IDM model to serve the total needs of their mainly industrial and automotive customers.

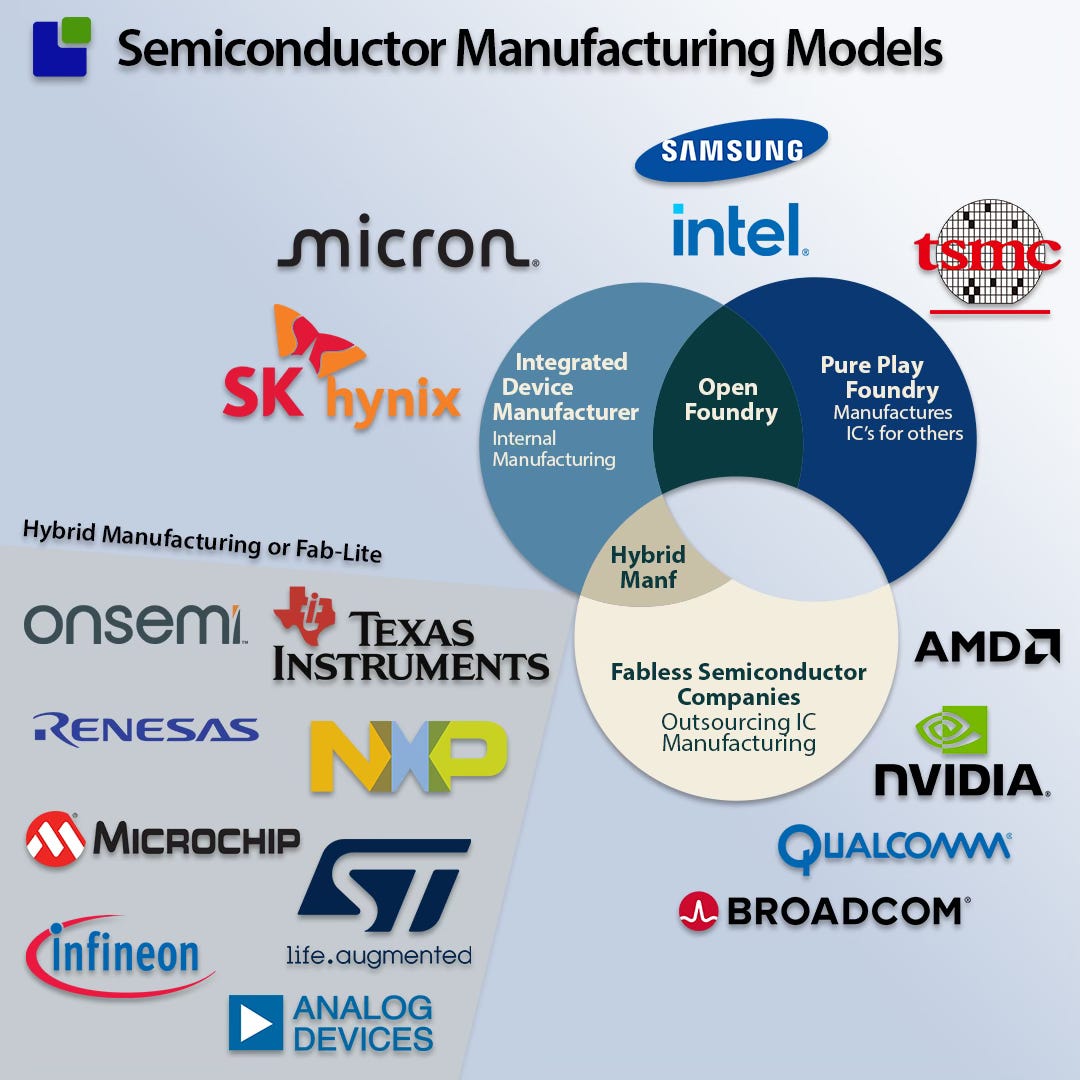

An overview of the industry manufacturing models can be seen below:

Lately, Intel has joined Samsung in making their capacity available to external customers in what has been named the Open Foundry model. The model could be more successful, but time will test its longevity.

It is time for a deeper dive into the hybrid manufacturing model.

As hybrids own manufacturing capacity, the balance sheet reveals the financial value of the fabs.

While the IDMs have significantly more fab value on their books, close to 22B$ for the average IDM (if that exists), the hybrids have fabs worth $6B on average and are spending 400M$ in CapEx.

The Hybrid model is a lot closer to the IDM model as can be seen in PPE turnover (The quarterly revenue generated by one dollar of fixed assets):

This does not serve as a comparison between the IDM model and the fabless; it merely demonstrates that a Hybrid Semiconductor company is often much closer to an IDM. This makes sense, as making a small semiconductor fab is impossible. Even the smallest ones are large and expensive.

Having established the perimeter of analysis, the business of the hybrids is ready for analysis.

Business status of the Hybrid Semiconductor companies

If you enjoy the updates from the semiconductor accountants from WSTS and SIA, you might think that we are now in the fifth quarter of recovery, and all is well. While we are five quarters into the Nvidia-driven AI boom, the reality for the industry's workhorses is entirely different.

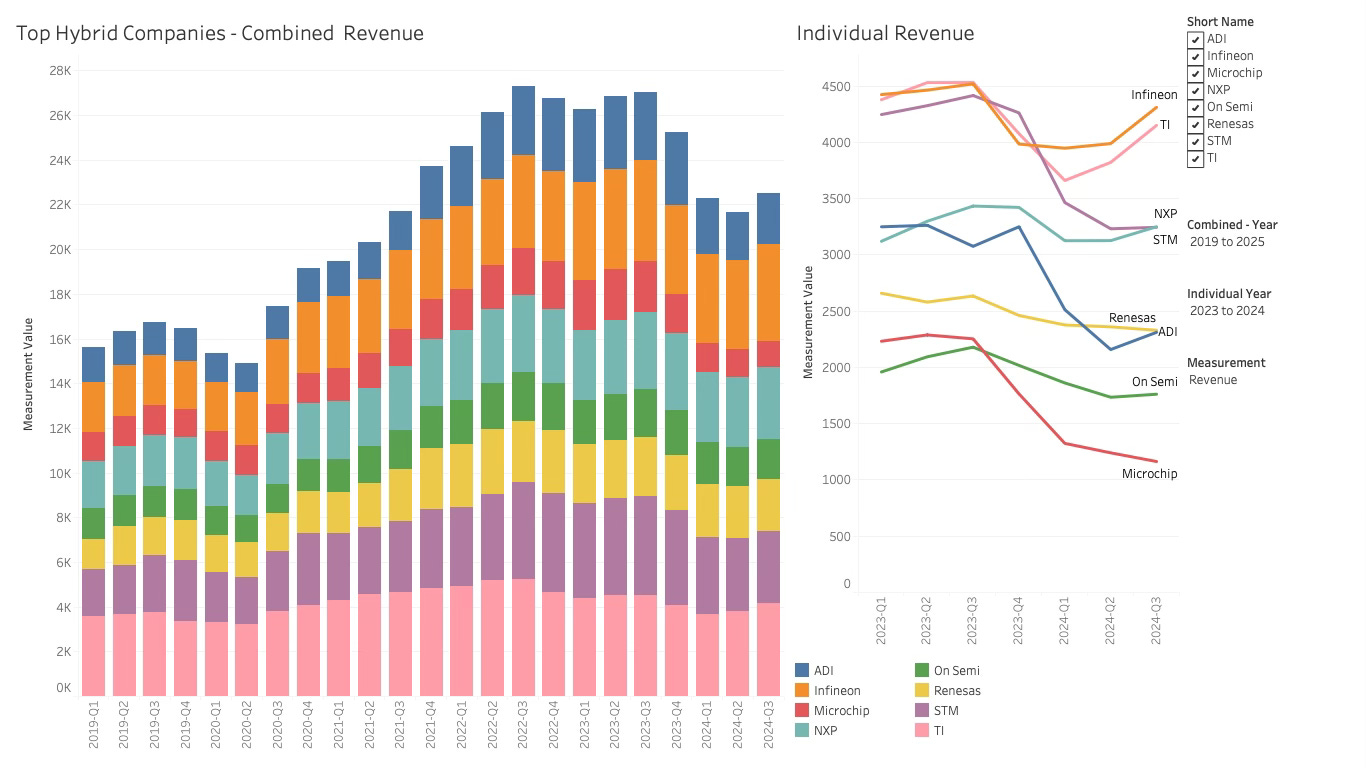

The combined revenue of the top 8 hybrid companies declined from a peak of $27.2B/Qtr to $21.6B last quarter. The 21% decline was steeper than the previous downcycle of 16%, where the downcycle took 7 quarters. The combined revenue grew 4% in Q3-24, suggesting the corner has been turned at the same time as last cycle. However, the guidance suggests this is far from the case.

While it looks like the corner has been turned, the guidance suggests something different. Led by Infineon, which expects a close to 20% decline, the collective dive is expected to be in the range of 5%.

The Overall Sentiment: Most companies express caution in their revenue guidance for upcoming quarters, reflecting macroeconomic uncertainties, inventory adjustments, and unpredictable demand. Customers are actively reducing inventory levels, impacting near-term revenue projections for many companies, particularly in the automotive and industrial sectors.

A significant factor is the macroeconomic weakness in Europe and North America, partially offset by resilience in the Chinese market, especially for automotive companies.

Pockets of Strength: The demand for AI server solutions is robust, providing growth opportunities for companies like Infineon, NXP, and STMicroelectronics.

As ADI, Infineon, and STM indicated, while facing near-term inventory corrections, the long-term prospects for silicon carbide (SiC) and other automotive electrification technologies remain positive. Microchip identifies aerospace and defence as a substantial growth segment.

Pricing: Increased competition (likely from China) and excess inventory are creating pricing pressure for new designs, while companies generally aim to maintain pricing stability for existing designs.

Corrective actions: To maintain profitability during the downturn, companies are implementing cost reduction measures, including operational expenditure (OpEx) cuts, strict cost discipline, and reduced capital expenditures (CapEx). Inventory levels are carefully managed to balance the need to support a potential upturn in the volatile market. Renesas is delaying the commercial production ramp-up at its Kofu factory and reassessing its SiC capacity plans. Infineon has also postponed the expansion of its Kulim 3 fab.

Despite the negative short-term outlook, all companies reiterated their faith in the longer-term outlook and strategies (surprise). Megatrends like AI, automotive electrification, and the increasing digitalisation of various industries will eventually pull the hybrids out of the gloom. Companies highlight continued investments in R&D, new product launches, and strong customer relationships as key factors supporting their long-term outlook.

Winners and losers

This headline should probably be called “losers and losers,” but as Cristine Legard of the ECB has said, “Never waste a good crisis.”

This is the optimum time to take market share.

TI and Infineon that have been competing for the top spot has been increasing revneue for the last couple of quarters and TI looks like the near term winner if Infineons guidance comes true.

Microchip and ADI have taken a serious beating but ADI seems to have turned the corner and returned to growth mode.

If we turn the focus to the share of the Total Hybrid Market (a more thorough analysis will follow) then the layered race become more visible.

TI and Infineon command just under 20% of the hybrid market. STM has fallen out of the leader team and Microchips situation becomes horribly apparent. There is a reason for the pay cuts.

Profitability analysis

Besides Net profits, the companies improved their other profitability from last quarter, demonstrating that the hybrids have adjusted their business model to the now eight-quarter-long depressed market and operate sustainably in this mode.

This is a testament to the resilient business model of the semiconductor workhorses, which ensures they stay profitable regardless of the circumstances. Even a company like Microchip, which has suffered a nearly 50% decline and had to make broad pay cuts, is still profitable in this depressed market.

The winners and losers in operational profits can be seen below:

This is highlighting TI’s strategy of maximising the generation of free cashflow has profound impact on its profitability. NXP has executed well and its revenue is only 5.7% the last peak. This is a stong position when the markets revive.

(This concludes the free section of the post. Paid suscribers get access to the advanced analysis, the conclusion and access to my dashboards. If you find value in my posts, I hope you will support my work by becoming a paid subscriber.)