The Silent Rotation Inside the Datacenter

The underlying shifts in the Datacenter Processing Market.

With AMD reporting, it is time to get an overview of the ground floor of the AI skyscraper. We already saw interesting reporting from the foundry basement that, despite a good TSMC result, suggests a pause in AI silicon shipment, which an overview might shed some light on.

This could be the following argument for or against the circular AI economy. So far, the discussion has certainly been as secular as it is circular. If a random datapoint enters the debate, it is quickly expelled with a warning: “How dare you challenge a good narrative with facts?”

While I don’t get entrenched in either camp, I will occasionally be in one or the other and don’t apologise for any swift changes in position. More things can be true at once.

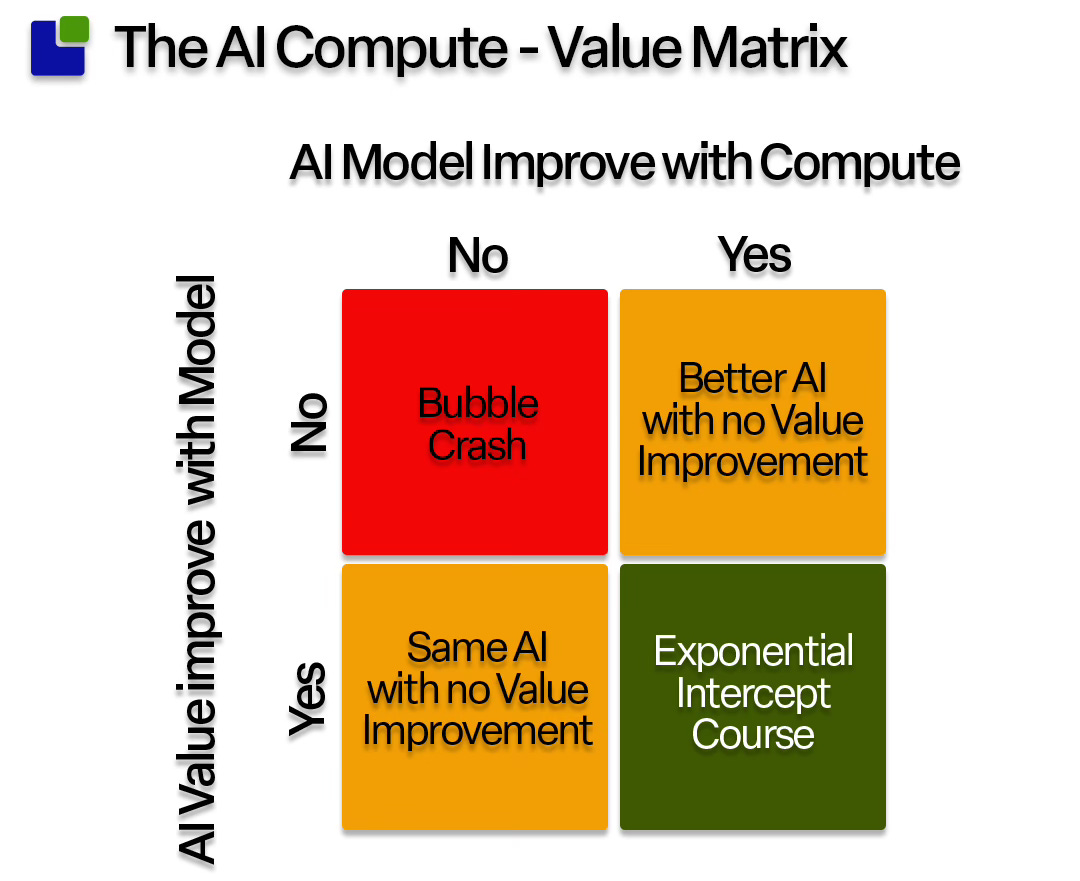

The discussion is framed as an either-or discussion. Either AI provides value or not, and if not, we are in a bubble. A slightly more nuanced perspective would be to break the question into two: Do AI models improve with compute, and does AI value increase with better models?

If you believe the question is the same, don’t worry—you will be fine. Go and buy or sell stocks accordingly.

The implied “DeepSeek” argument that AI models can improve independently of compute is not actually the same as stating that models will not improve with more compute. It is adding another dimension to AI growth through model improvement. This argument has been used to predict that compute infrastructure is irrelevant and models can improve without compute. This will be like inventing the perpetual motion machine, and it sounds pretty insane to me.

Another argument that circulates is that most enterprises are not seeing any value from AI initiatives. While these statements are derived from qualitative research and lack insights about scale, they can certainly be true.

But this is not the same as stating it will never be true. If AI value improves with compute, value from AI will grow, and eventually, even corporations with their wasteful management models will be able to derive value from AI. It might be too late, as startups have AI at their core rather than as a department under Legal and HR.

Having observed the incredible development of the AIs I follow, there is no doubt in my mind that AI is providing value and will be even more valuable in the future. If that is the case, the argument needs to be viewed temporally: When will AI provide value?

Rather than the circular vs linear discussion, the AI revolution should be seen as an exponential evolution like the good old days in the semiconductor industry. Eventually, exponential growth will intercept everything. Maybe even the valuation of your favourite AI stock.

The exponential improvement in AI models and in accelerated compute combined will create wonders not only in Chatbots but also in physical AI, Science, and all aspects of daily life.

Exponentiallity

Before diving into the analysis of the data centre compute market, it is worth noting the exponentiality derived from the silicon basement of the AI skyscraper.

One of my guiding principles has been that whenever I observed something exponential, it was almost certainly due to semiconductors as defined by Moore’s Law.

The exponential increase in performance, decrease in power consumption, and price created miracles throughout my career.

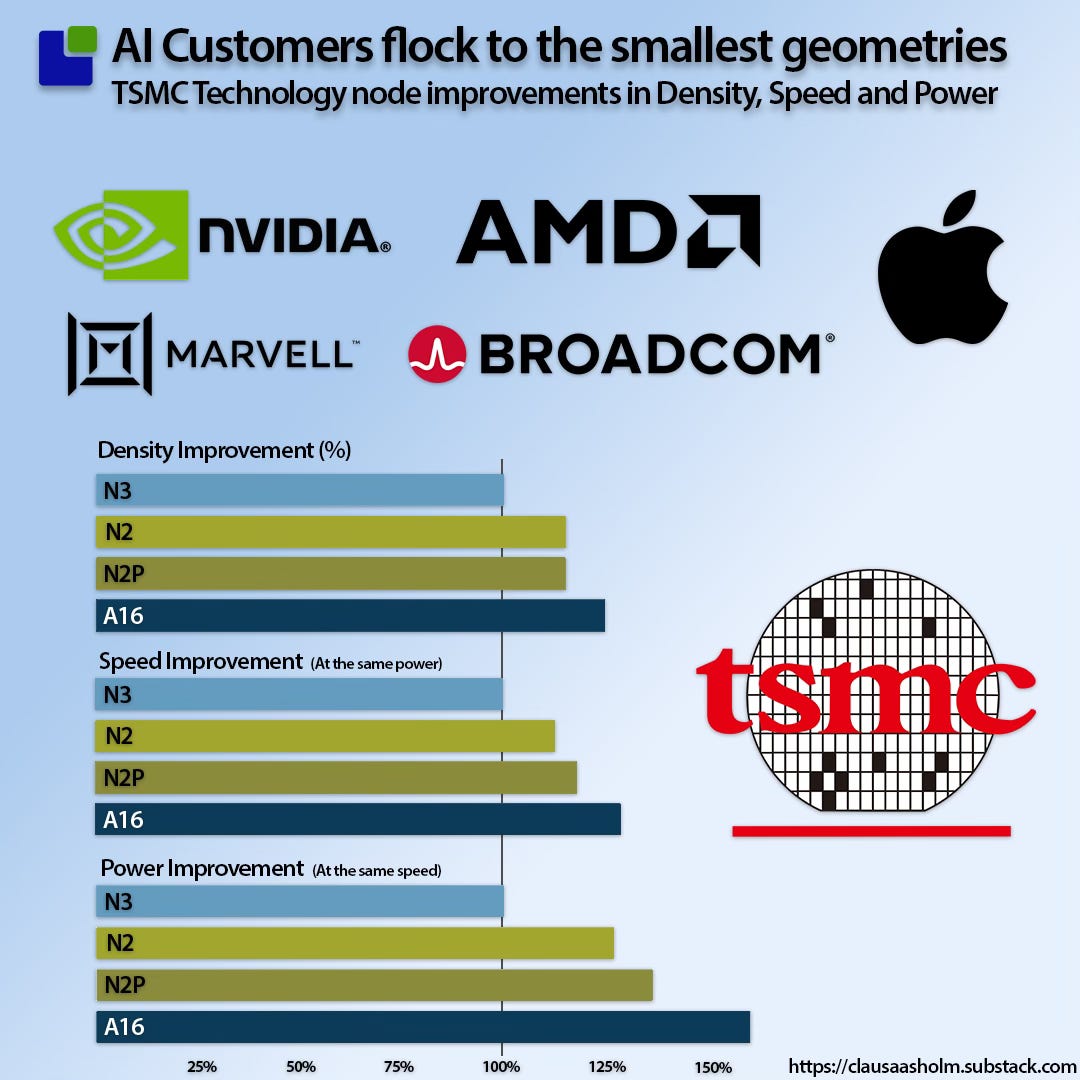

However, Moore's law is running out of steam, and while this has happened before, we are approaching boundaries that are hard to breach. They prevail despite architectural, optical, and packaging innovations that drive further improvements.

As can be seen, TSMC is still improving through the introduction of new node technologies. Still, they are not at scales that justify the valuation increases of AI, Cloud, and Semiconductor companies.

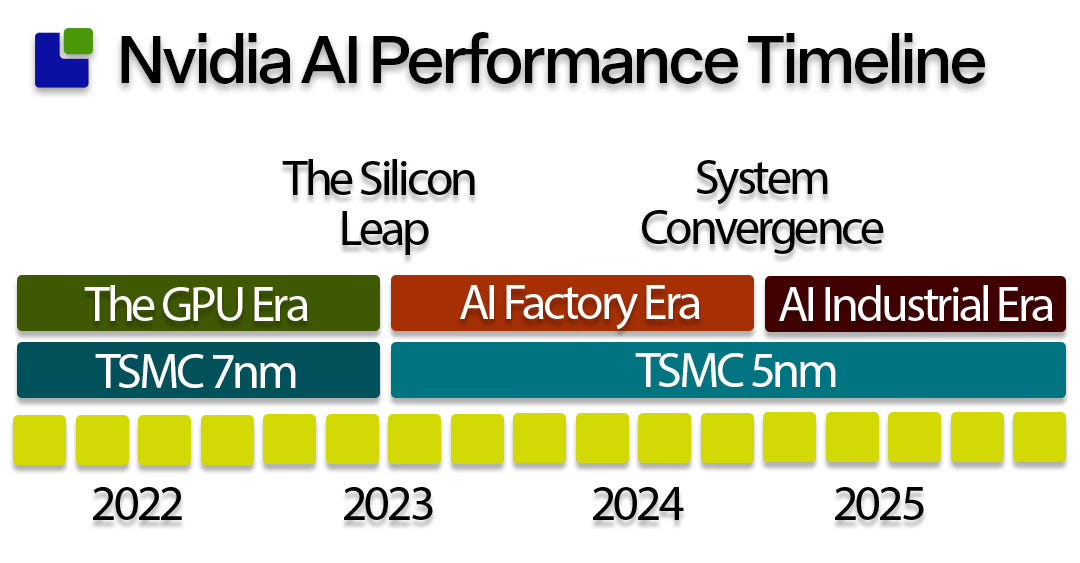

The exponentiality has moved somewhere else.

You don’t need to listen to Jensen Huang for long before you realise that, for Nvidia, the exponentiality now resides in accelerated computing. He certainly has a point, as Nvidia’s current success is based on a technology that is less advanced than what is in the back pocket of a teenager's baggy jeans.

The latest node jump Nvidia made was from the A100 on TSMC 7nm to the H100 on TSMC 5nm, and while that also signalled the beginning of the AI era, the performance improvements since then have not been driven by advances in node technology.

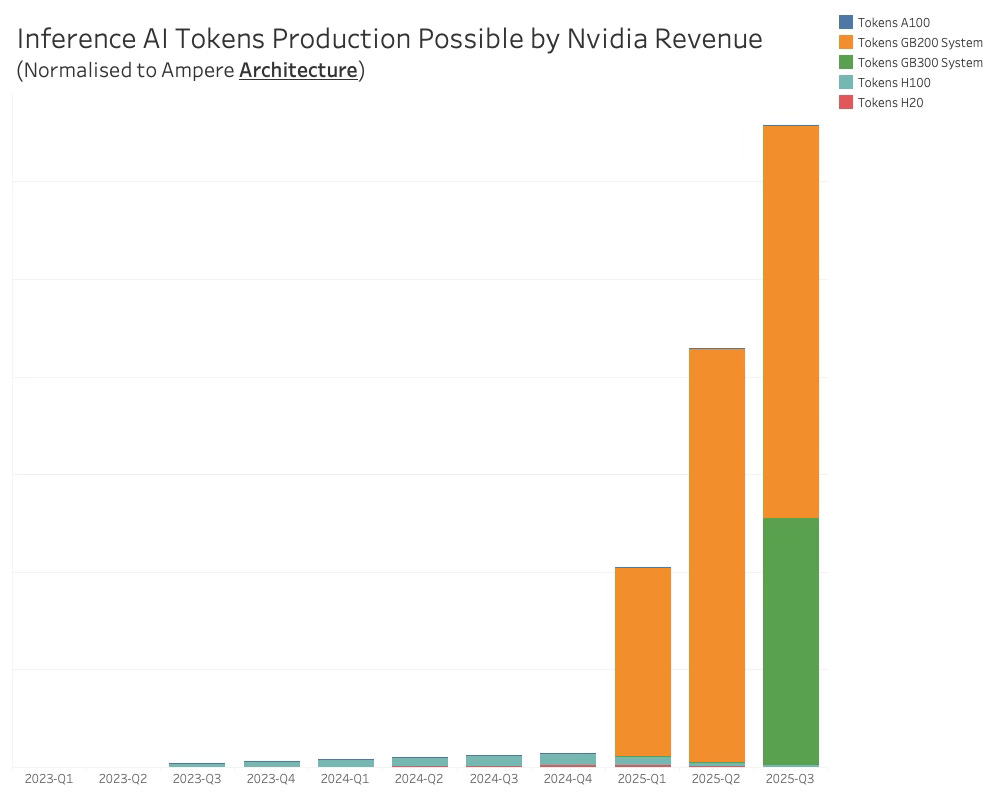

While I will deal with the revenue implications of these shifts later, it is worth getting an overview of what these shifts mean from a computational value.

The best definition of compute is a token as described below

A token is a discrete unit of text or data, as defined by a model’s tokenizer, that represents the smallest piece of input or output the model processes.

(Source: OpenAI Documentation, 2023)

A token is roughly what it takes for an AI model to process four letters of English text. This also means that anything measured in tokens must be expressed in scientific notation, and clarity will be lost in translation.

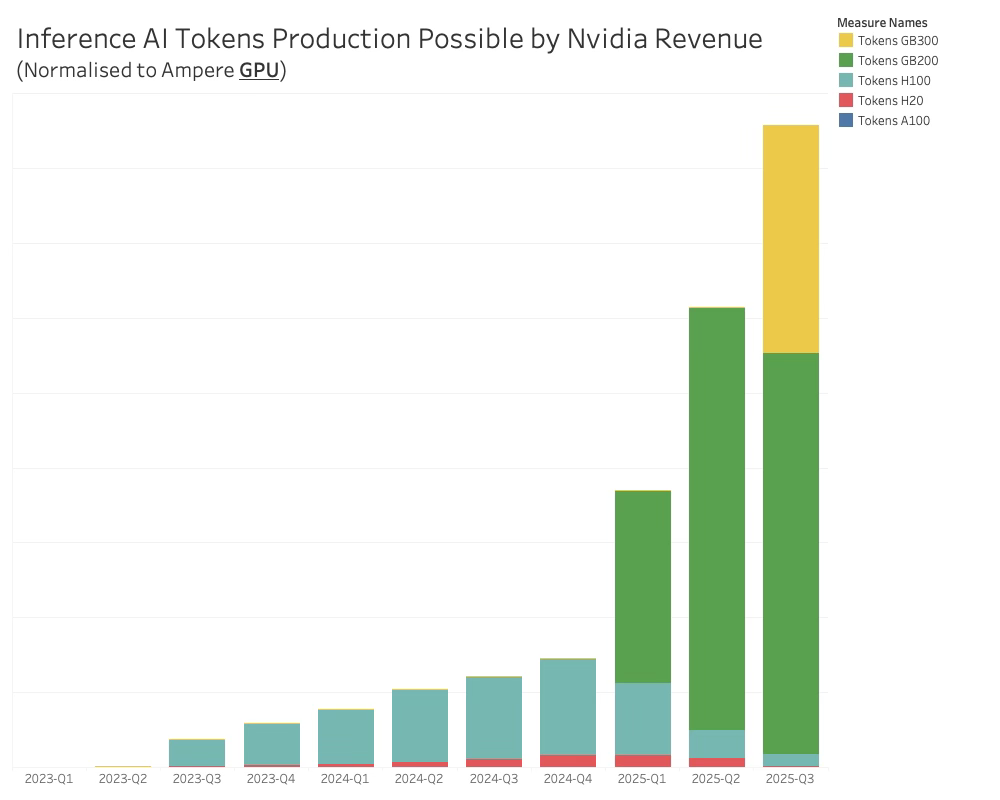

For clarity, I have invented the Ampere Token, which equates to the tokens you get from 1M$ invested in the Nvidia Ampere architecture, representing the GPU era.

This is roughly 135K Tokens/sec (depending on architecture, workload and all the other performance gymnastics used in technology marketing).

With this definition, the compute performance generated by Nvidia related to the GPU itself is as follows:

While these are approximations based on rough performance metrics, the performance increase from the GPU design alone is staggering. The Ampere performance is virtually invisible, and the H100 step in Q3-23 that began the AI revolution looks puny.

But it gets better (or worse if you are Michael Burry). If you wonder why Nvidia bothered to upgrade the GB200 to GB300, even though it is based on the same B200 Blackwell GPU, it is because of the gains from system improvements. Improvements in Memory, interconnect, rack topology, and power/liquid cooling led to a massive increase.

While not based on benchmark data, but anecdotal information from presentations, modelling the systems improvement effects gives the following token performance:

The AI systems era represents a more significant leap than the silicon leap. The AI Factory era is barely visible.

Suppose you wonder why Nvidia is introducing a new architecture annually and has no problem selling it to the same customers. In that case, the answer is here, even if this is a rough calculation.

This is worth bearing in mind when diving into the actual revenue and market shares of the datacenter compute market.

As usual, I am getting ahead of myself, and while I am in the process of decaffeination, my delusions are fading enough to get back into dollars-and-cents mode and begin my review of the Datacenter compute market.

The Datacenter Compute Market

In my analysis, I divided the compute products into three separate elements that are tightly knit together. For this analysis, I treat compute as whatever the 5 semiconductor companies in the analysis report as compute.

While you might have an urge to educate me on the right way to conduct an analysis, I have to remind you that I am unincorporated and don’t have a boss. I don’t really care about what is seen as correct or complete analysis - I am focused on useful analysis which can take many different forms.

That said, you need to understand the definitions of your analysis and when it is useful and when it is not. I will let you be the judge of usefulness for you.

The data centre compute market began as a component market, where server companies originally bought Intel CPUs, memory, and other components for fixed-format server boards that integrators could use to build data centres.

With the emergence of AI GPUs and high-bandwidth memories, it became possible to build tightly knit GPU boards with several processing units and stacks of HBMs.

Mounted on different substrates, the tightly knit system would have lower latency and higher performance.

This is the default today for AI GPUs—they are no longer GPUs, but GPU subsystems. The WSTS concept of a semiconductor device dates back to the last decade. Nvidia took this a step further, introducing the H100 GPU and a full AI server rack while maintaining H100 GPU boards for server companies to build their own server systems. The pricing of the H100 boards meant Nvidia maintained a similar level of value capture as when selling a server system. In reality, Nvidia is pretending to compete with itself.

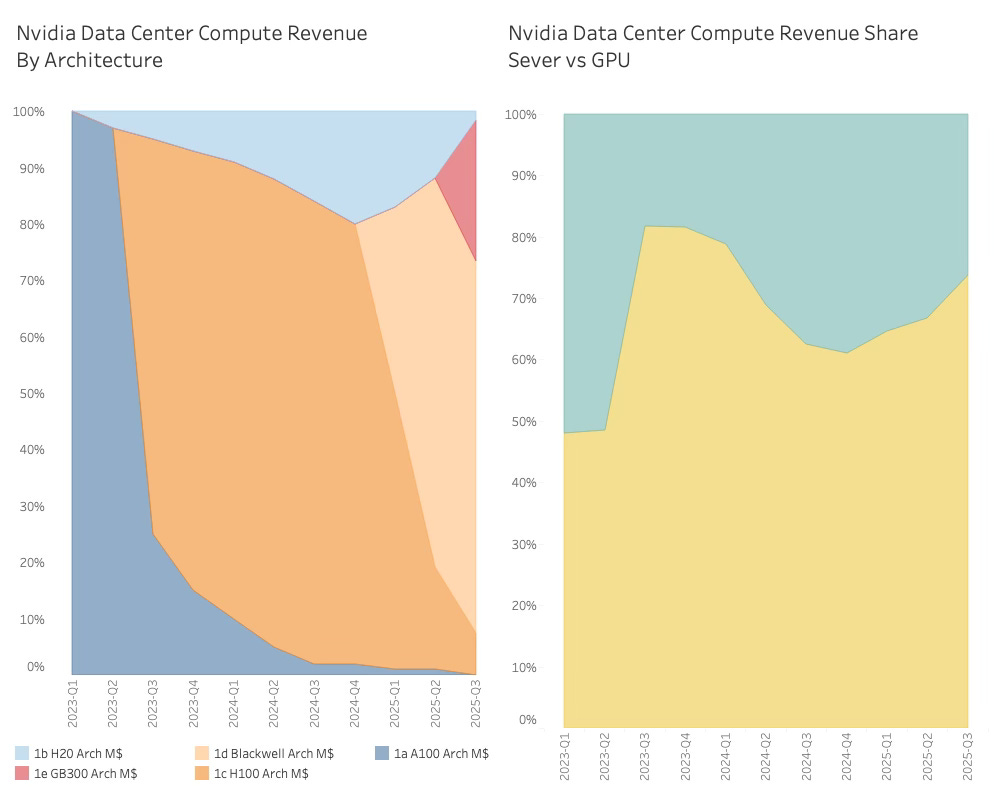

Nvidia revenue by architecture and Server/GPU board is shown below.

The revenue from rack-scale systems is closing in on 75%, and the rapid succession of architectures is very evident.

Today, the AI GPU leader is on its third generation of servers, while AMD is preparing its first version —the Helios Server rack, currently being showcased.

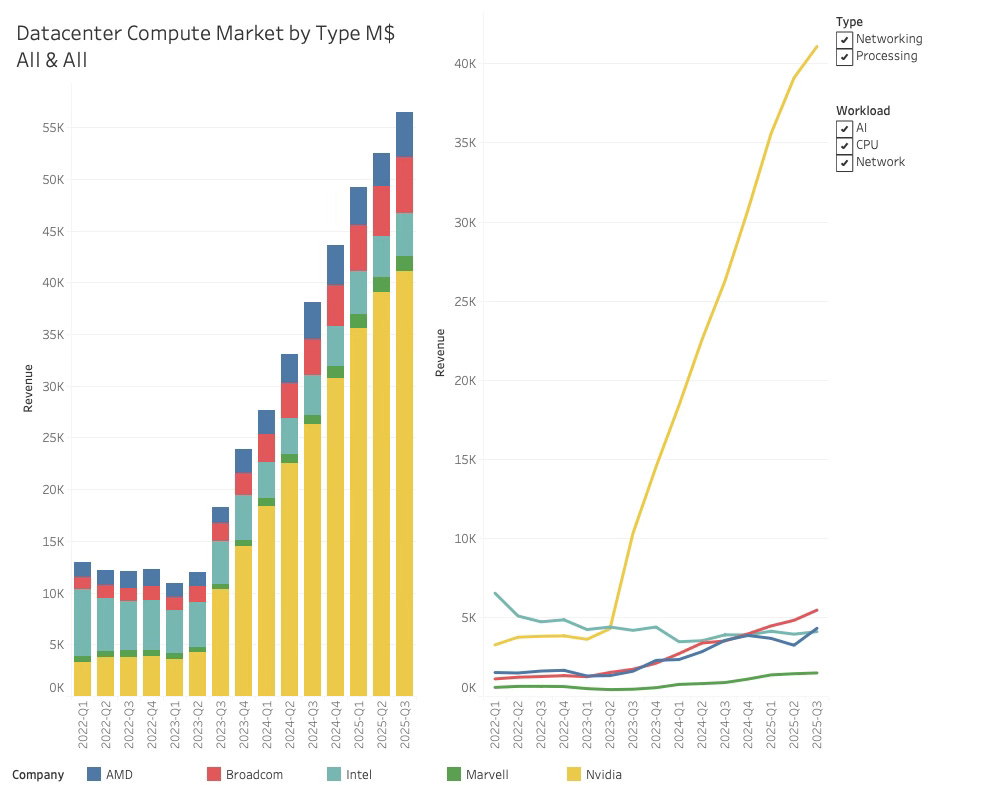

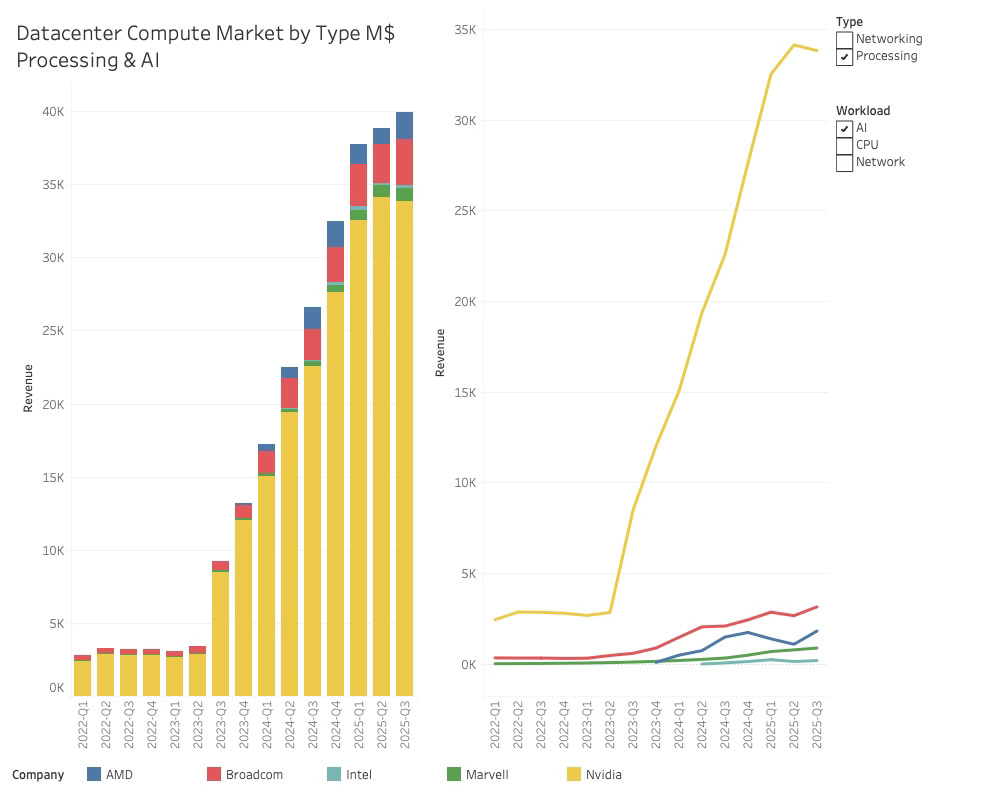

Bearing this in mind, the compute revenue in the datacenter compute market looks like this:

As Nvidia's dominance continues, Broadcom is beginning to make meaningful gains, while AMD is back in third place again. Intel is still too busy patching holes in its hull to worry about market shares.

While there was a lot of chatter about the CPU workloads benefiting from the AI revolution, the datacenter CPU revenue is not really on a significant growth trajectory:

The CPU workload revenue is 19% lower than what it was at the beginning of the decade, adding to Intel's long list of problems. The 60/40 split in Intel's favour has been pretty stable over the last 6 quarters, and nothing suggests a dramatic change is underway.

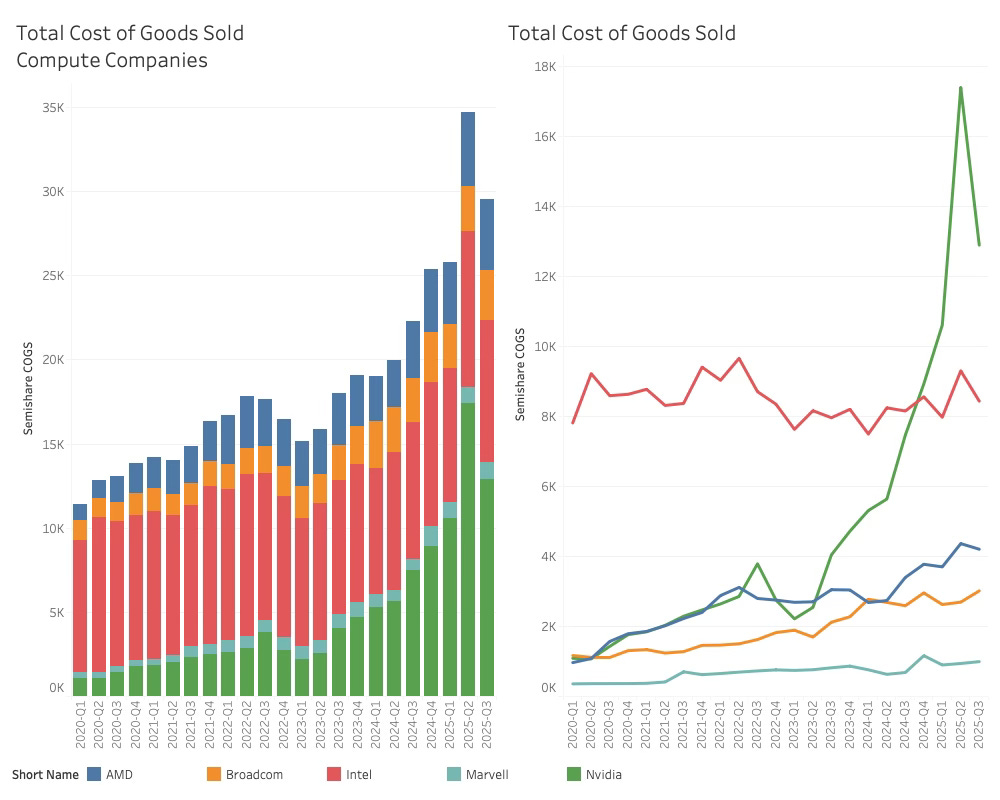

This should also be seen in the context of Cost of Goods Sold, as Nvidia’s profits are enormous. COGS shows a different situation.

While Nvidia accounts for 73% of Datacenter revenue, it accounts for only 41% of total COGS (ignoring the fluke H20 writedown in Q2-25). This includes all the products sold by the companies, but we can see that the AI unit sales are more comparable to the CPU unit sales, while the revenue favours the AI giant.

The overall growth in data centre compute might not be surprising, but the development in AI processing revenue that excludes networking and CPU workloads is somewhat more interesting.

The AI compute revenue of the five companies is now on a new and much lower growth trajectory than before.

This could pose a problem for the valuation of both hyperscalers and the Semiconductor companies that sell to them, notably Nvidia.

Some of this is down to the embargoes on Nvidia's sales to China and similarly for AMD's MI308. The total revenue impact for Nvidia can be seen below: