The Evolving Datacenter Compute Market

Will Nvidia be outcompeted by its customers? Can the Green Giant coexist with the emerging accelerator architectures?

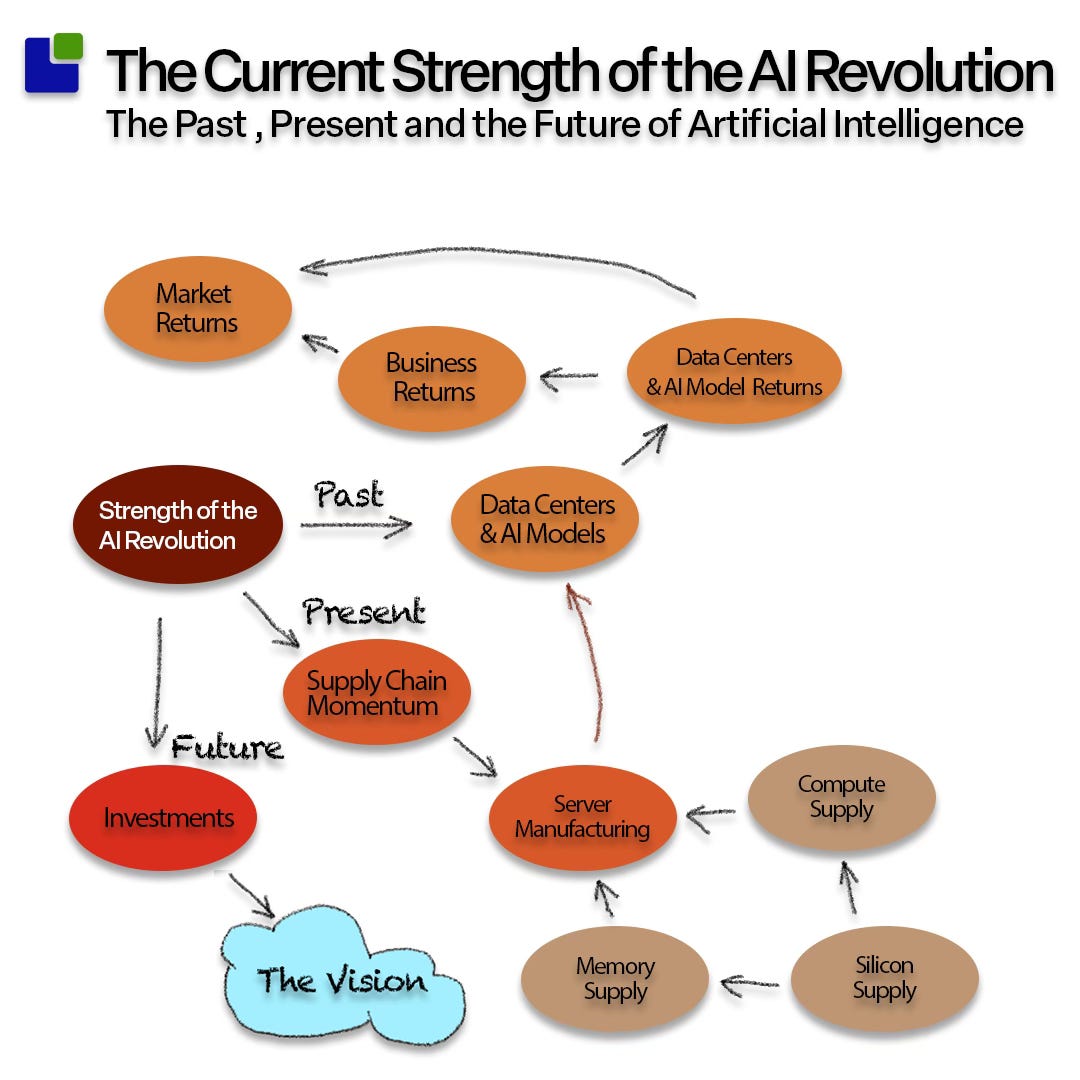

To understand the current strength of the AI revolution, I have had to extend the analysis across three posts, following the question structure outlined below.

The two other posts can be found here:

It is now time to delve into the semiconductor sector of the AI revolution and understand the current state of the AI supply chain.

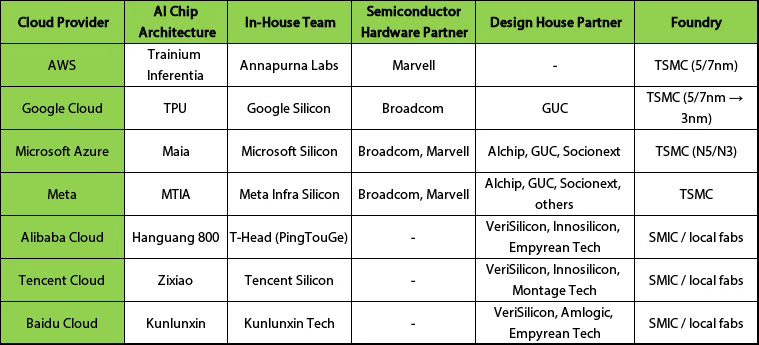

There are two main supply channels of the compute supply. One is the GPU/CPU-based compute supply chain, which includes Nvidia, AMD, and Intel; the other is the custom accelerator supply chain that each of the large hyperscalers has for their own proprietary architecture.

The design side of AI Chips

While hyperscalers began designing their own accelerators before Nvidia's rise to the forefront of AI, each of the top Western hyperscalers does not rely solely on its own architectures but also buys a significant number of Nvidia servers.

Even if they would like to avoid buying the high-margin Nvidia servers, they are needed for several workloads focused, but not limited to, training. The hyperscaler strategy is to move as much of Nvidia’s server workload as possible to its own accelerators.

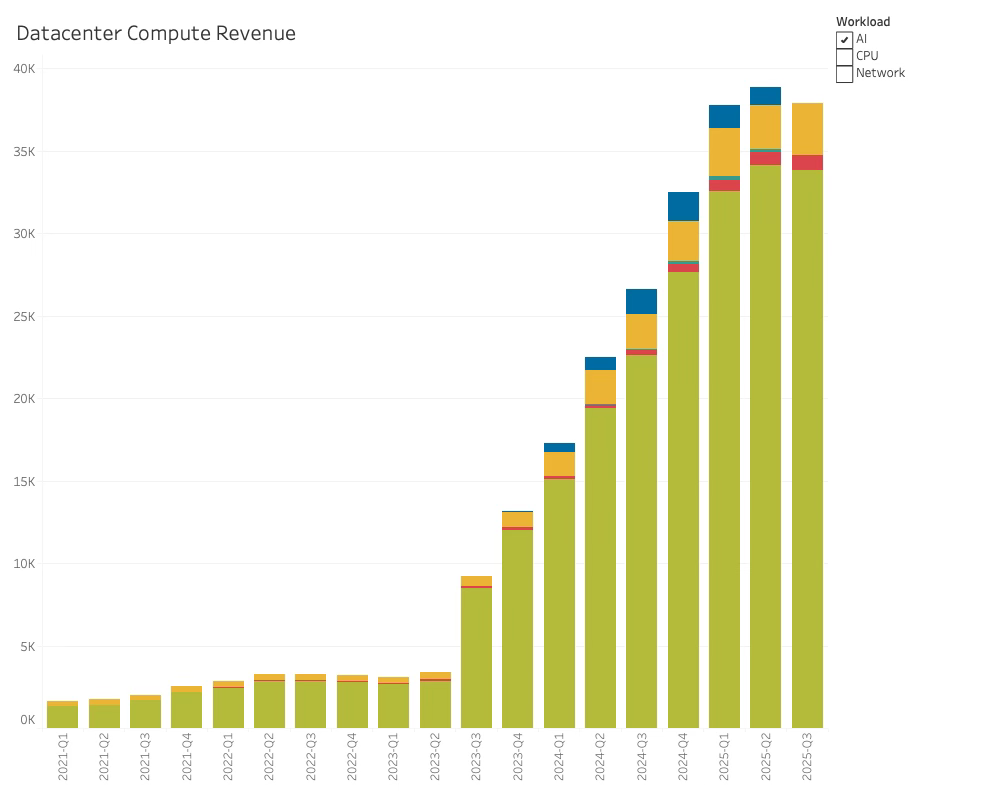

The narrative that this is a binary choice is false. Nvidia’s revenue is unlikely to plummet as hyperscalers transition to their own architectures. The two supply tracks have been coexisting since the first TPU design back in 2015, and the balance of power is not about to change in favour of the accelerators.

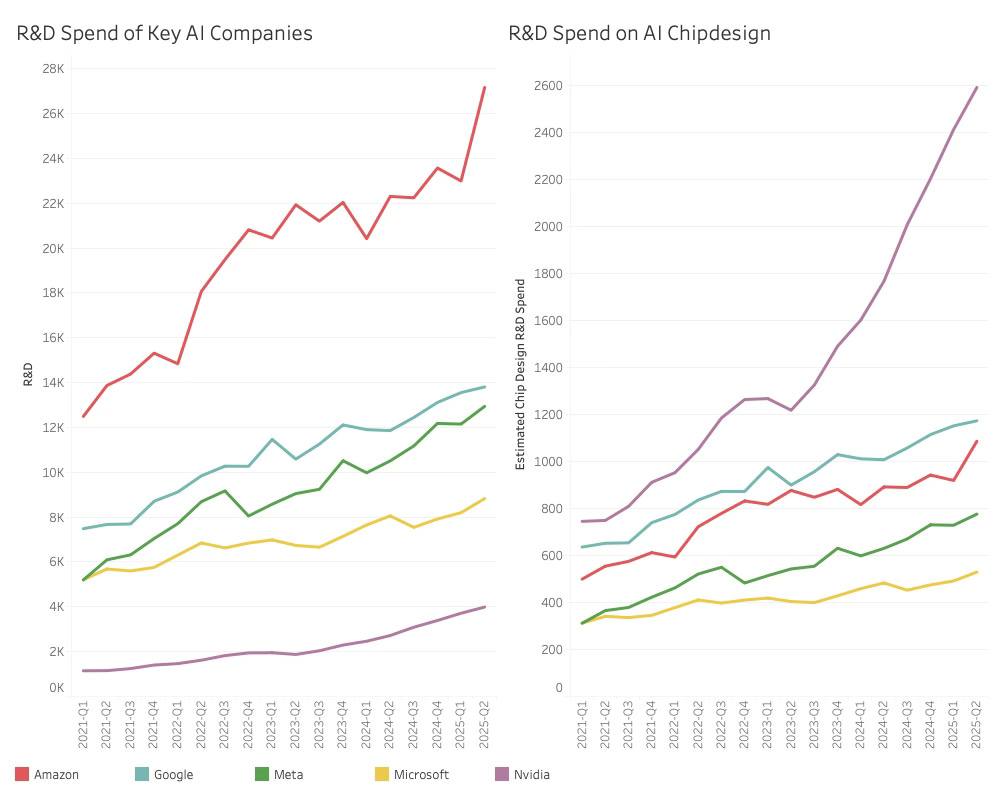

While the R&D budgets of the hyperscalers are significantly larger than Nvidia’s, their AI Chip design budgets are not. An analysis of the estimated R&D spend on Chip Development shows that while Nvidia spent the most, the R&D spend was 42% of the combined R&D spend of the hyperscalers just a couple of years ago.

Last quarter, it had grown to 73% of the combined spend of the top 4 hyperscalers. Nvidia will soon outspend all of them, leaving little room for the “Nvidia is doomed” narrative.

The recent spike from Amazon was not related to AI hardware. Amazon explicitly cited AI-related initiatives as a key reason for increased investment. These include projects such as expanding Alexa+ to more customers, optimising the DeepFleet robot, and developing agentic developer tools. They also stated that most of their AI efforts are focused on enhancing customer experience, operational efficiency, and accelerating innovation. These require heavier investment in software and new product development.

Another research angle of the self-sufficiency supply channel is to understand the supply chain differences of the supply tracks. The supply chain map can be seen in this post:

A key difference in the two tracks is the use of external design resources to enable the proprietary architectures.

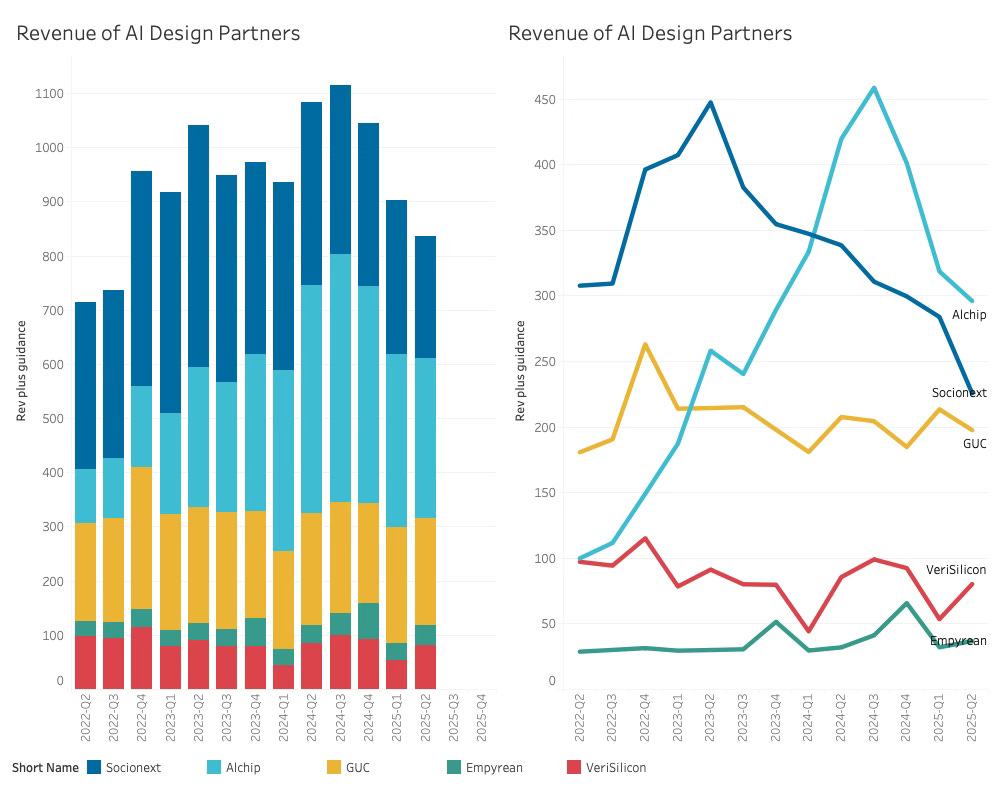

In the early phases of the AI hardware wave, design houses such as Alchip and Socionext experienced a surge in business. Hyperscalers needed partners to help translate ambitious chip architectures into manufacturable designs, and backend specialists filled that gap. Their revenues rose sharply as Microsoft, Meta, and others pushed multiple new accelerators through tapeout. Yet despite the explosive growth in AI compute demand, those revenues have recently declined.

Investigating Alchips’ reporting does not suggest a fundamental shift in how hyperscalers are using design-houses, and the revenue decline can be attributed to specific programs, although the customers are not disclosed.

First, shipments of a 7-nanometer AI accelerator to a North American customer came to an end. Second, demand for a 5-nanometer AI accelerator slowed more abruptly than expected, leaving Alchip with a gap in production revenue. Additionally, a critical 3-nanometer AI accelerator tape-out was postponed from the second quarter to the early part of the third quarter, pushing expected sales out of the reporting period.

Although Alchip never names its customers, it is possible to make an educated guess by looking at industry timelines. The conclusion of a 7-nanometer program lines up with either Google’s TPU v4 or Amazon’s first-generation Trainium, both of which were manufactured at TSMC’s N7 process. The slowdown in 5-nanometer demand aligns with the production cycle of Google’s TPU v5, which has been in production since 2023. The delayed 3-nanometer tape-out appears to correspond to either Google’s upcoming TPU v6 or Amazon’s Trainium2, both next-generation accelerators expected at TSMC’s N3 node.

While the hyperscalers may have poached some talent for their internal teams, there is no indication that they are abandoning the design houses, which could suggest a slowdown in design activity at the hyperscalers.

This is in sharp contrast to Nvidia's one new architecture a year cadence. With declining design house revenue, there are no indications that the Hyperscalers are going to overtake Nvidia while they are carving out workloads they can serve with their own designs.

Data Centre Compute Supply.

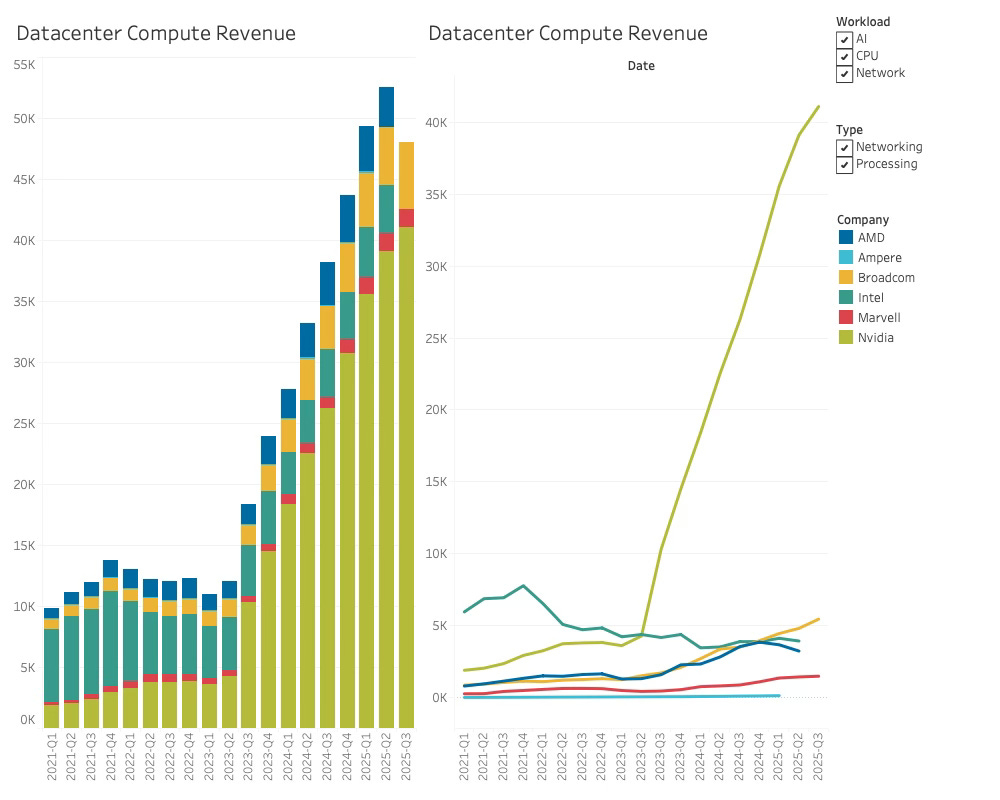

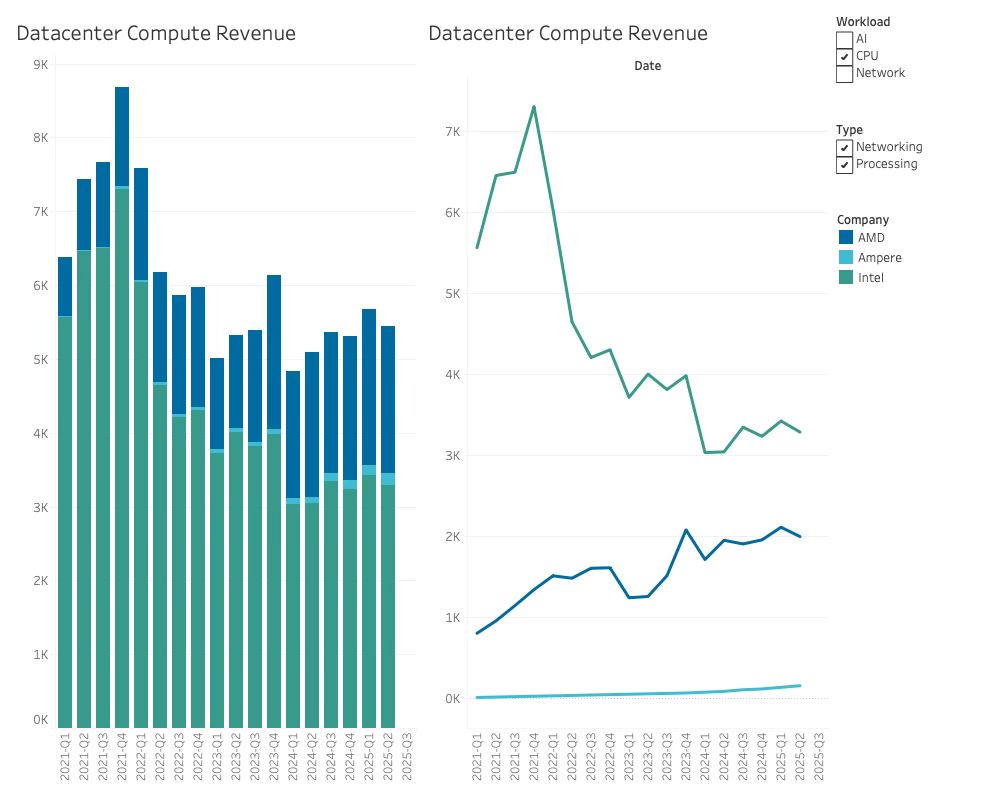

It is hard to remember that just over two years ago, Intel was still the leading supplier of computing power to the data centre. From a dominant 78% share at the beginning of the decade, the market share declined to 36% just before Nvidia’s first blowout quarter with the H100.

Two years later, Intel’s revenue in the data centre is 10% lower, and its market share has shrunk to 7.5%.

As is typical in corporate decline, the disruption did not originate from within, but rather resulted from a shift in the market structure of the data centre industry.

When you observe your management spending 99% of their time analysing the internal revenue and funnel data, you can be sure they will never see the truck coming.

That AI has eaten Intel’s lunch is not news, but adding insult to injury, the CPU business of data centres is now smaller than the networking consumption, and that does not include Nvidia's own consumption, as will be shown later.

As the CPU data centre revenue declined, Intel's revenue was also attacked by its long-time rival AMD. The two companies have reached an equilibrium, with a combined revenue of $5.5 billion, where Intel holds the larger share.

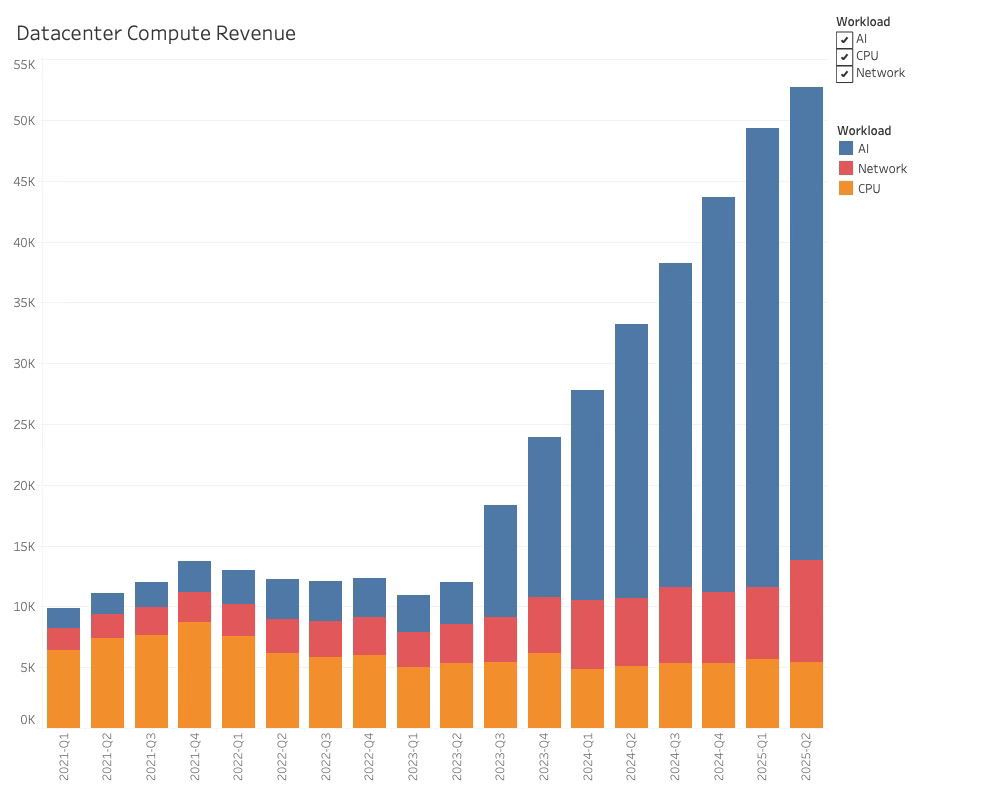

While the GPU datacenter market has experienced dramatic growth since the launch of Nvidia’s Hopper architecture, the growth has been declining, which could signal a weakness in the AI revolution, as can be seen in the GPU revenue below: